Queen Anne’s alleged lesbian affairs take centre stage in the award-winning film The Favourite, while the politics that wove through her reign is merely a back drop. Even the War of the Spanish Succession, in which Britain won Gibraltar, has little more than a walk-on part. The religious rifts that still threatened to shatter the country – a century after the Catholic Guy Fawkes tried to blow up the Protestant James I/VI of Scotland and his Parliament – are all but ignored.

So too is the man who would become the star of the sectarian disputes, a preacher known across the length and breadth of the country for his fiery rhetoric, a scourge of the establishment and an ecclesiastical celebrity – in terms of name recognition, he was the Olivia Coleman of his day – Dr Henry Sacheverell.

The Queen was not present at the newly built St Paul’s Cathedral in London for the traditional thanksgiving service on the morning of 5 November 1709 – two-years after the Act of Union joined England and Scotland – and her absence could be felt. The usual crowd of eminent Londoners had gone to the service in St James that she was expected to attend. The congregation at St Paul’s, therefore, was sparse when an obscure young preacher climbed to the pulpit. Most of those who came to hear Sacheverell on that autumnal Saturday would have expected the usual attacks on Catholics and the obligatory praise for Protestantism. Few could have predicted that the preacher was about to become the most famous man in the country.

The doctor’s face was a ‘fiery red’, said William Bisset in The Modern Fanatick a few months later, and there was a ‘goggling wildness of the eyes’ when he began ‘working himself up into a frenzied anger’ thundering away ‘against the whole battery of his favourite targets’. These included not just Catholics, but atheists and dissenting Protestants such as the Quakers and Presbyterians as well as those members of the ruling Church of England that Sacheverell thought were their allies. ‘He was,’ wrote Bisset, ‘transported with an (sic) hellish fury.’

The denunciations escalated. Sacheverell even attacked the chief minister of the day, Sydney Godolphin, by alluding to his nickname, ‘Volpone’, (‘sly fox’ in Latin). ‘Godly Godolphin’, as the Lord High Treasurer was also known due to his virtue, was a keen chess player and a compulsive gambler, particularly on horses. He bred, raced, and even ate them. He was at the centre of all the big political battles of the age, chief among them his government’s prosecution of the war, known in the United States as Queen Anne’s war.

The last of the Stuart monarchs, Queen Anne was fat, gouty, frequently ill, and addicted to brandy. She had 17 pregnancies, but none of her children lived beyond childhood.

Her government was run by the Whigs, a party that believed in an interventionist foreign policy, rights for religious dissenters, and limits on the power of the monarchy. Tories like Sacheverell supported the Church of England, a strong Crown, and isolationism. The Tories drew their support largely from the country gentry, while the Whigs were more popular among the urban merchant class.

Jumping on the beds

The parties had emerged in the reign of Charles II, Anne’s uncle. The Whigs had wanted to exclude her father, James II, from the succession because of his Catholicism. The Tories had supported his divine right to rule. They won, but James alienated all the major interest groups within three years, and was deposed by his eldest daughter and nephew, Mary and her husband William of Orange, in the Glorious Revolution. The couple became the first ‘joint monarchs’ as William III and Mary II, and were the first to swear an oath that they would govern constitutionally.

Mary didn’t seem to lose much sleep over usurping her father. She arrived at Whitehall Palace, his former residence, ‘Jolly as to a Wedding’ and in the same air of excitement reportedly jumped on all the beds.

Both Whigs and Tories had agreed to the ‘Glorious Revolution’, but the former were more supportive, the latter more reluctant. When Mary died from small pox six years later, it left a foreigner, William III, as king in his own right (he was a grandson of Charles I through a maternal line), while the deposed James II and his young son were in exile. James’s supporters, the Jacobites, actively tried to restore the old king. An assassination plot in 1696 targeted William III after his morning hunt near Kew. The plan was to shoot him as his coach and six went down a narrow lane near Turnham Green on its way back to Westminster. But one of the plotters betrayed the others and on the day, the King took a different route. Nine traitors were arrested, tried, and executed.

In the end, the Jacobites didn’t need an assassination. William died only six years later after his horse, Sorrel, tripped on a molehill, throwing the king and breaking his collar bone. In the pubs and taverns of England there was rejoicing among the king’s enemies and toasts to ‘the little gentleman in the black velvet waistcoat’ that had dug the deadly hill. The poem An Epitaph upon a Stumbling Horse was dedicated to the king’s mount, praising him for his role in the regicide.

A proudly headed Nag he was,

And hence it often came to pass;

Tho’ he his Feet nought valued,

He still stood much upon his Head.

William was succeeded by James II’s second daughter, Anne, placating some Tories but doing little to appease the Jacobites. Sacheverell was a strong proponent of divine right and also a militant supporter of the Church of England, of which Anne, unlike her Calvinist brother-in-law, was a strong supporter. According to some of his enemies, Sacheverell was a Jacobite who ‘had drunk the Pretender’s Health several Times’. However, he seems to have supported Anne. He published a Sermon, The Political Union, on her accession (seven years before his St Paul’s sermon), in which he commended her divine right to the throne and encouraged his followers to ‘Hang out the Bloody Flag and Banner of Defiance’ protecting the church from Whigs, atheists, dissenters, and Catholics.

"The bloody

flag officer"

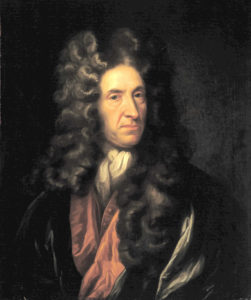

- Daniel Defoe

Sacheverell’s militancy and natural confidence got him noticed. He soon got the nickname ‘knight of the firebrand’ due to his reputation as a demagogue and shameless self-promoter. Daniel Defoe, author of Robinson Crusoe, called him ‘the bloody flag officer’.

Defoe was himself no stranger to pamphlet disputes, having had his arms and head locked into the pillory as a result of a seditious libel the year after Anne came to the throne. The pamphlet that got him into trouble may have been inspired by the likes of Sacheverell, as it was a deliberately over-the-top mockery of similar high-church clerics, even advocating hanging for dissenting priests. Embarrassingly the satire was endorsed by other high-church clerics, not realising it was mocking them. In the end, the rain kept the crowds at bay and those that did show up threw flowers instead of rocks or rotten fruit.

Sacheverell’s fiery disposition may have been overcompensation for his own background, which was not as Tory as he would have people believe. Many of his relatives were dissenters and one of his direct ancestors, Henry Smith (after whom Sacheverell may have been named), was a signatory to the death warrant of Charles I, the great Tory martyr whom Sacheverell had praised in his St Paul’s sermon.

To his fellow academics at Oxford, where he started his career, and others who heard him preach, Sacheverell was not easily forgotten, nor easily warmed to. Although tall and handsome, and particularly attractive to women, he had a deeply unpleasant character. The 20th Century Professor Geoffrey Holmes, in The Trial of Doctor Sacheverell, bemoans his search for anyone who ‘genuinely liked or admired him’. Later when he was awaiting his trial the Doctor ‘failed humiliatingly’ to get any senior figure from Oxford to write a ‘testimonial of his good life and character’.

The Church in danger

But he possessed two notable positive traits - energy and dedication. It was probably because of these that he attained his Doctorate of Divinity at 34, decades earlier than some noted theologians at the time. Later, when he was canvassing for the lucrative chaplaincy at St Saviour’s in Southwark, London, he put so much zeal into his campaign that he had to be sent back to Oxford to cool off. When he eventually got the position, he celebrated in a characteristically immodest style by drinking with cronies and verbally abusing his rivals for the post.

With such a reputation, his elevation to the national stage of St Paul’s was unlikely to be greeted as anything but a provocation by the Whig government. The choice of preacher was in the power of the Lord Mayor of London, Sir Samuel Garrard, a fanatical Tory. Garrard had also served in Parliament and was one of the infamous ‘tackers’ who tried to attach anti-dissenter clauses to an unrelated bill. At one general election, Tories like Garrard and Sacheverell tried to paint the Church of England as being ‘in danger’ and used it as a rallying cry against the Whigs. Gerrard’s actions in Parliament earned the ire of Godolphin who called him the most ‘perverse man in the whole house’.

The cathedral where Sacheverell preached that autumn morning had been consecrated only the year before, though services had been held there for 12 years previously. Scaffolding and other evidence of workmen could be found inside and out. Yet a foreign traveller remarked on seeing the building that ‘it is already so black with coal-smoke that is has lost half its elegance’.

In contrast to the venue, Sacheverell’s words were not new, the doctor had delivered almost exactly the same sermon four years earlier, during the ‘Church in Danger’ campaign. They had got little notice then. In both sermons, Sacheverell not only berated his enemies in church and state, he also seemed to attack the Glorious Revolution itself and in particular the Whigs’ use of it to give more rights to dissenters.

The Doctor and his troublesome sermon might have been completely forgotten had things moved in a different direction. But Lord Mayor Garrard invited Sacheverell to dinner where he encouraged the preacher to print his sermon. Sacheverell had already visited several eminent lawyers who had assured him there was nothing in it liable for prosecution. Gerrard later applied to the Whig-dominated Court of Aldermen, whose blessing was customary before publication. When they refused, Sacheverell went ahead anyway.

His sermon to a few hundred people in St Paul’s became an almost instant best-seller. By the end of the affair, 100,000 copies had been circulated. Holmes has estimated that as many as a quarter of a million people may have read it which meant it ‘had no equal in the early eighteenth-century’. This would have been magnified still further by the huge number of newspapers, pamphlets and periodicals reporting on the affair. In Queen Anne’s reign, 2.3 million copies of newspapers were circulated every year. Like today’s singers and actors, clergymen were often well-known in a world where religion dominated daily lives. Sacheverell however, was in a different league, a star was being born.

The Whig government seemed to hope that their own writers would destroy the Doctor’s sermon through ridicule, mocking its inaccuracies and the bombast of his style. One writer wrote how the Tories had been ‘routed’ in the paper war. Many Tories seem to have been embarrassed by the Whig response and it was several weeks before someone bothered to pen a defence of Sacheverell.

A vain, haughty, egotistical, arrogant, and flamboyant figure

As the affair wore on, professional muckrakers went into Sacheverell’s less-than-savoury character and background, revealing a vain, haughty, egotistical, arrogant, and flamboyant figure whose ‘Vices [were] too many to be all singly spoken to’. Critics descended on his life in search of skeletons. It was said that he loved ‘his Bottle’ as much as the Church, once drinking at an inn from ‘Nine at Night, ’till Ten the next Morning’. After one hard night, he and a colleague apparently fell into a saw pit a situation he only managed to get out of after a hefty struggle.

Stories emerged of him as a young man, failing to get ordained because he refused to concede errors in his Latin and how he attacked a cook with a shoulder of mutton. His militant intolerance and hatred of dissenters also emerges; He refused to pay his washer woman a debt of 7s 6d once he found out she was an ‘old Presbyterian’. He is said to have shaken the woman roughly and called her other names.

After such an intense character assassination, impeaching him on a charge of ‘High Crimes and Misdemeanours’ might have looked like overkill. But the Government’s decision may have been influenced by the effect Sacheverell was still having on the populace, who were, among other things, fed up with the war in Spain and the Netherlands. The sermon may have caused outrage among the educated elite, but to the public he was a hero, protecting the Church and fighting the establishment. According to Holmes, when people heard he was to preach at St Margaret’s Lothbury, London, before the Commons vote on impeachment, the building was packed, and the baying mob outside was so large that it threatened to ‘pull down doors and break the windows’ to hear him.

To the public he was

a hero, protecting the

Church and fighting

the establishment

Impeachment has a long history in English law as a way for the House of Commons to check the power of ministers and officials. It is not surprising that the early framers of the US constitution took inspiration from these measures. In English practice, the House of Commons would draw up the articles (charges), vote on whether to impeach, and appoint managers (prosecutors) of the case. The House of Lords then hears the case and votes on the articles to determine guilt.

Court case or carnival

The Commons agreed on 15 December, less than six weeks after the sermon, to impeach, and the trial was set for the following February. After the vote, Sacheverell enjoyed a remarkably comfortable month in custody. He was detained not in a prison, let alone the Tower, but in the lodgings of the Commons’ Messenger in Peters Street, Westminster. Compared to the jails at the time, where criminals, debtors, and children as young as four were housed under appalling conditions and often exploited for profit, Sacheverell was living in luxury. A hamper of claret and 50 guineas arrived from the Duke of Beaufort, followed by numerous friends and well-wishers publicly paying their respects.

He was released on bail in January. A huge mob appeared at his church the next Sunday, expecting him to preach. They were disappointed, however, as the Doctor was busy writing an answer to the charges against him.The government didn’t get everything its way either. It had expected the matter to be settled quietly at the bar of the House of Lords. But they lost a vote in the Commons and had to accept a full public trial with all its pomp and ceremony. This guaranteed public anger would only get worse as Sacheverell had the chance to play a new role – that of public martyr.

The start of the trial in February was arguably more like a carnival than a court case. Entrance was by ticket only, with about two thousand people in total being accommodated on the huge scaffolds designed by Sir Christopher Wren, the architect of St Paul’s itself. The trial was to take place in Westminster Hall (today, the oldest surviving part of Parliament), an imposing medieval structure, redecorated with elaborate angels by Richard II. This was a far larger and more fitting location for the spectacle. Seats had been reserved for foreign ambassadors, the managers, and judges. The Queen and her ladies of the bedchamber had private boxes. Sarah, the Duchess of Marlborough (played by Rachel Weisz in The Favourite), is known to have joined the Queen in attendance

Sarah was Queen Anne’s friend and confident. Rumours were already circulating that the two were lovers. Evidence for this was scant at best. True, they had pet names for each other – the Queen was ‘Mrs Morley’, Sarah was Mrs Freeman. And they did have fights, which the rumour mill described as ‘lovers’ tiffs’. During one public dispute over the jewels Anne should wear to a church service, an impudent Sarah told the Queen to ‘hold your tongue’, a shocking thing to say to the Lord’s anointed monarch.

Were Mrs Morley and Freeman lovers?

Politically, Sarah was a known Whig and loathed Sacheverell’s High-Church stance. Her husband, the Duke of Marlborough, was Commander in Chief of the army, suggesting she also supported the war effort. As in The Favourite, Sarah and Anne would eventually fall out, with the former being replaced by Abigail Marsham (Emma Stone), but at the time of the trial they were still confidants.

The atmosphere the Queen and her friend would have found at the trial was electric. The crowds chattered loudly, mostly to find out whether their neighbours were for or against Sacheverell. This almost came to blows a couple of times. In one incident, a woman offered a man a piece of cold chicken (the customary snack at a trial) only to whip it away when she found out he was against the Doctor, declaring ‘I’ll have my wing again’.

With pomp and pageantry the Commons filed in to the hall in pairs, the Scots members – rather to their annoyance – being placed last. This ceremony was repeated every day. The 119 Lords would appear later in their ermine-trimmed robes and in order of precedence. After everyone was assembled on the first day, the Clerk read the articles of impeachment.

Article I concerned Sacheverell’s attack on the Glorious Revolution, Article II was to do with his condemnation of acts promoting toleration for dissenters (perceived as an attack on Parliament), Article III regarded the suggestion that the Church was in danger, and Article IV was about his criticisms of individuals in the ministry, particularly ‘Wily Volpone’ Godolphin.

The Duchess staged a dramatic intervention during the recitation of the charges, descending from her box to sit with the members of the Commons, right next to the managers of the trial, indicating her support for Sacheverell’s prosecution.

'Monsters and Vipers in our Bosom'

Despite his bombastic and overbearing demeanour, the Doctor had been smarter with his Sermon than his opponents at first thought. The legal advice he had received seemed to be broadly watertight and the prosecutors were forced to concentrate on only a few paragraphs where they believed that Sacheverell had slipped up. But their team contained some brilliant minds who were able to use what small ammunition they had.

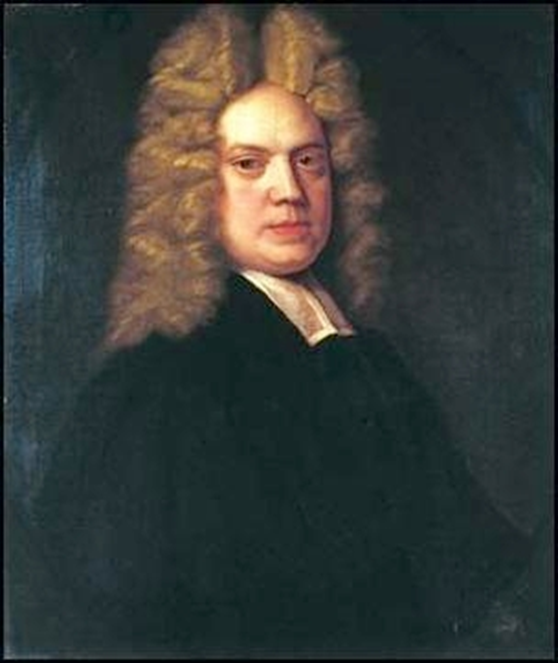

The MP and military commander General Stanhope accused Sacheverell of being a ‘tool of a party’ and of preaching politics in order to incite people against the Government. Robert Walpole, who would go on to become the first British Prime Minister, claimed the sermon masked a ‘Poisonous pill’ by implying the Glorious Revolution was ‘Illegal’. They also highlighted his fanaticism by quoting his own words back at him, namely that laws protecting dissenters nurtured ‘Monsters and Vipers in our Bosom’.

Walpole’s arguments in the trial propelled him to nationwide fame. A flamboyant figure who was nicknamed ‘brass’ because of his rustic nature, he would later gain a reputation for corruption and vanity. His taste for luxury almost led to his imprisonment for debt, and after the fall of the Whigs he would be imprisoned in the Tower for embezzling 500 guineas while Secretary of War. Unusually for the time, Walpole and his wife, Catherine, in effect had an open marriage. After the death of Queen Anne it was rumoured that Walpole had encouraged his wife to have an affair with the new Prince of Wales, the future George II.

The drama inside the court was equalled if not exceeded by what was happening outside. People were being forced to choose sides in what was fast becoming the most talked about event of the decade. Marlborough’s grandson wrote to him to say that he had been to the trial every day and was ‘against’ Sacheverell. Sir Justinian Isham, on a trip down from his native Northamptonshire, reported that ‘all the conversations in town run upon this trial’ and that all other ‘publick or private concerns, are quite laid aside’.

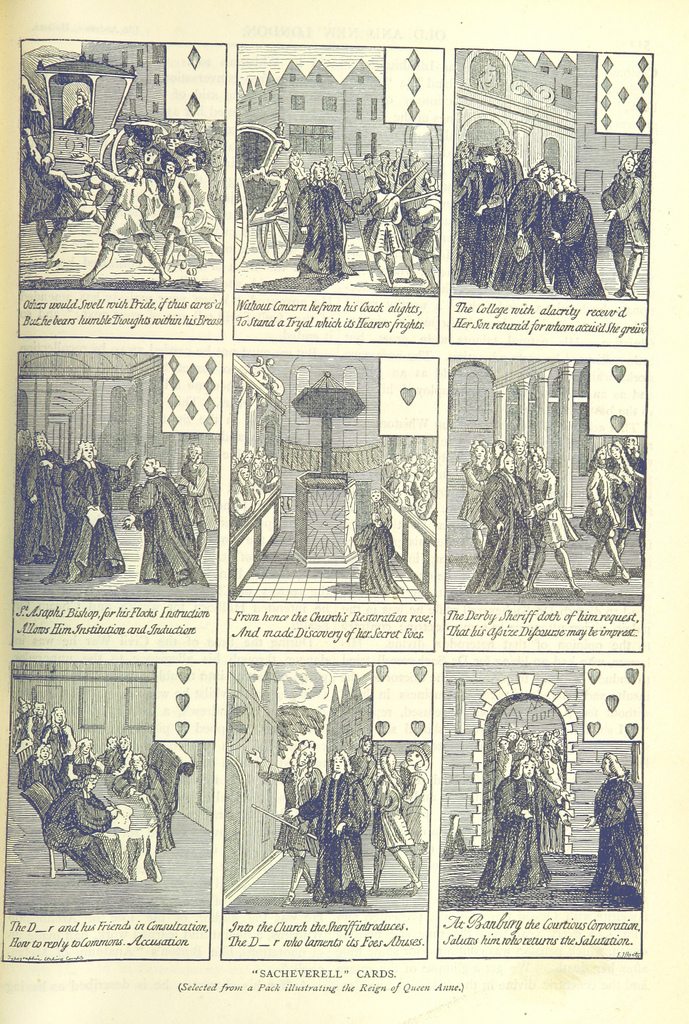

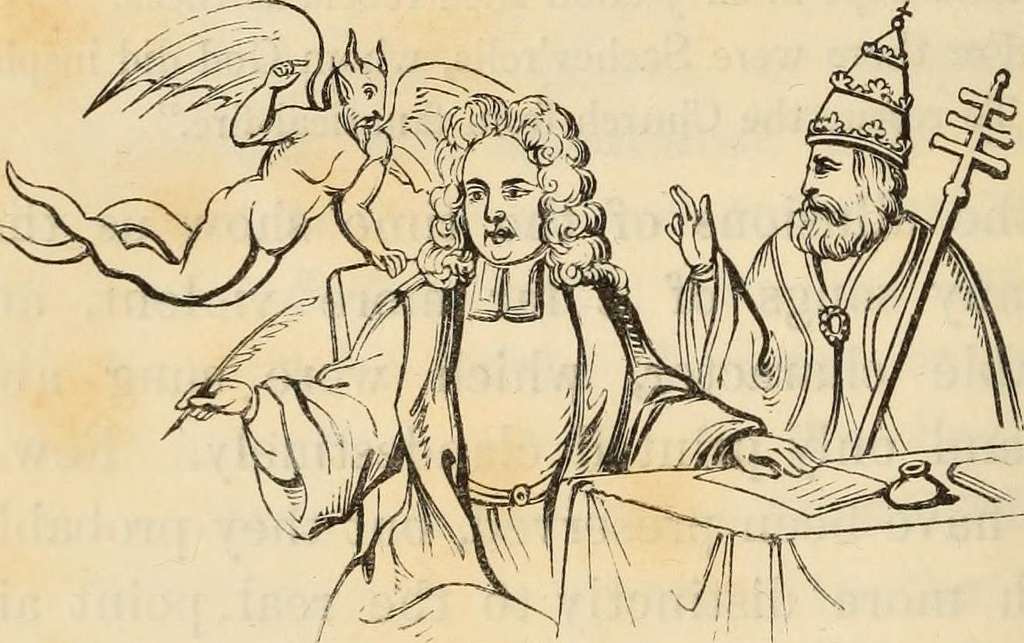

Pamphlets, ballads, newspapers and satirical prints debating the issues began to appear. An updated portrait of the Doctor had been painted during this period, prints of which were sold. Eager to cash in on the clergyman’s celebrity, enterprising businessmen looked for ways that Sacheverell’s supporters could openly back his cause. His effigy began appearing on seals, fans, handkerchiefs, snuffboxes, medallions, playing cards, and figurines.

Pamphlets, ballads, newspapers and satirical prints debating the issues began to appear. An updated portrait of the Doctor had been painted during this period, prints of which were sold. Eager to cash in on the clergyman’s celebrity, enterprising businessmen looked for ways that Sacheverell’s supporters could openly back his cause. His effigy began appearing on seals, fans, handkerchiefs, snuffboxes, medallions, playing cards, and figurines.

Women were particularly taken by the defendant. Sacheverell, a bachelor, reportedly received several marriage proposals, many from wealthy ladies (thanks to private donations from well-wishers, he was already free of money worries). Even prostitutes in St James Park whispered ‘are you for the Dr?’ before accepting a client. A satirical print, titled THE Modern IDOL or Kiss my A-se is no Swearing, mocked this devotion, showing Sacheverell surrounded by female admirers with a verse starting:

These Figures act a Tory Farce,

Quite mad to kiss the D-ters A-se.

His br-ches are already down,

In no Small danger is his Gown.

Some of these women may not have been quite so accommodating if they knew Sacheverell’s attitude to the opposite sex. The Doctor was supposed to have said ‘tis no Sin to lie with a single Woman, and no great one with a married’ and in terms of matrimony, Bisset contends that ‘his long Celibacy is not the Effect of Continence, but a Dread of Confinement’.

The attacks were not just one way; with the trial a national sensation, the Whig managers themselves became frequent targets. One Whig newspaper claimed that ‘a manager of the tryal’ was aggressively ‘pusu’d’ by a crowd and that the Tory press coverage was motivated by a desire ‘to mark them out to be assassinated and murdered’.

The night of fire

Building on the intolerant themes already preached by Sacheverell, the mob had become more resentful towards dissenters. The crescendo of this anger led to the ‘night of fire’.

For ordinary members of the public who could not get into the court the only way to see Sacheverell was during his morning trip from his lodgings to Parliament. Typical for a man known for his vanity and theatrics, these had turned into almost imperial processions. The Doctor’s coach went deliberately slowly so he could lap

up the acclaim, sticking his hand out of the window to be kissed. The crowd that followed him home in the evening could be even larger – some estimated it to be in the thousands. At his door, Sacheverell would ‘put his hat off to the mob’.

After the prosecution rested its case at the end of the third day of the trial, the crowd was in a particularly violent mood and ‘assaulted and affronted’ many of the managers, throwing mud at them as they left the court. When they arrived at the Doctor’s lodgings it was clear that many were armed for action, carrying crowbars, pickaxes and other makeshift weapons.

Their first target was a prominent dissenter, Daniel Burgess and his Presbyterian meeting house, which was pulled down and stripped of anything of value. The furnishings were piled up and put to the torch. Many in the crowd performed a ‘ritual dance’ before throwing their loot on the fire. Burgess escaped with his life through the charity of a neighbouring Catholic. One witty ballad that was circulated at the time captures the public mood perfectly:

Invidious Whigs, since you have made your Boast,

That you a Church of England Priest would roast,

Blame not the Mob, for having a Desire

With Presbyterian Tubs to light the Fire.

Similar scenes were repeated all over the city, with items looted as well as burned, all carried out to a chant of ‘High Church and Sacheverell’. In Hatton Garden, the builder of one meeting house was dragged from his bed and only saved himself through a bribe, the crowd deciding to symbolically burn his ‘night-cap’ instead of him. Others used the rioting as an excuse to rob people, particularly those that did not immediately shout ‘God bless Doctor Sacheverell’.

It took four hours for the Government to act, motivated in the end by their fear for their own possessions. The Earl of Sunderland (one of the Secretaries of State) sought an audience with the Queen who, at great personal risk, agreed to lend him her own troops (there was no time to raise the militia and there were few regulars in London). Not until the early hours were the soldiers able to restore order and the city remained on edge for the rest of the trial, troops patrolling the streets and roughly a hundred suspects in prison by the following week. There was a suspicion, although never proved, that Sacheverell and his Tory patrons were directly involved.

The remainder of the trial, in which the defence presented its case, was overshadowed by the Night of Fire. Sir Simon Harcourt, the chief defence council, was on characteristically good form as he tried to explain away some of Sacheverell’s more bizarre pronouncements and intemperate language. It was pointed out many times that ‘not a single article against him contained a direct quotation from his sermons’. Evidence was produced that amply justified Sacheverell’s views on many of the articles portraying them as fairly standard Anglican views (despite the difference in the colourfulness of the language).

Harcourt was a lawyer and MP who frequently took time off from the Commons to go on the legal circuits. His oratory was legendary. Arthur Onslow, who was later the Speaker of the House, described him as possessing ‘the greatest skill and power of speech of any man I ever knew in a public assembly’.

The most memorable part of the defence, though, was Sacheverell’s own speech. It must have stunned the crowd when he adopted a ‘conciliatory tone and more moderate position’ – no trace of the haughty and self-promoting showman that people had come to expect. It was a brilliant piece of theatre, which drew tears ‘from the eyes of men and women’ and even kept the attention of Queen Anne, who had attended every day of the trial.

Her Majesty's view

The sympathy of the crowd mattered little in this case. The Lords would decide, and they were a fickle bunch. The Government nominally held a majority in the Upper House, but the deciding factor was likely the Queen’s view. She was thought to support conviction too, and did nothing to suggest otherwise. Sacheverell was eventually found guilty on all four Articles.

All that remained was to sentence him. There had been talk of imprisonment, a fine, or a lifetime ban from preaching, defrocking – the removal of his priestly status – or a corporal punishment such as birching. But the Queen was thought to want a lenient sentence, and the Whigs were aware that none of the stiffer penalties would be acceptable to the Lords, let alone the mob. They were forced to concede to suspending Sacheverell from preaching for three years, and the public burning of his sermon. Sacheverell was not even barred from being promoted while banned, allowing the Church to reward him for doing no work at all.

The melting away of their majority in the Lord’s was a huge embarrassment for the Whigs, many on the opposition smelt blood and it was not long before the old regime would be swept away. Over that summer, most of the important figures in the Ministry were eased out of office, replaced by Tories. The new Tory ministry decided that – to capitalise on Sacheverell mania and their new found influence with the public – they would call an election.

The general election of 1710 turned a Whig majority of 69 into a Tory one of 151. There is little doubt that Sacheverell was the reason. His prosecutors were routed at the polls. Even a war hero like General Stanhope, who was the last general in European history to kill an opposing commander in single combat, was defeated by a local brewer in the seat of Westminster. Walpole himself failed to secure his seat. The Norfolk crowd that pelted him ‘with dirt and stones’ also jeered him with cries of ‘No manager’, referring to his role in the trial.

Drinking the Doctor's health

Although banned from preaching, Sacheverell made a typically immodest spectacle by going on a stately progress around the country to celebrate his lacklustre ‘punishment’. Everywhere he went, people drank the Doctor’s health and huza’d him and bells were rung. In some places bread was distributed with the mark Sacheverell 1710 and several children throughout the country were christened ‘Sacheverell’. Effigies of his enemies were burnt, dramatic parades into towns were staged with many being little more than an ‘elaborately staged electioneering exercise’. It was clear that Sacheverell favoured Tories wherever he went and few were under any delusions about the Doctor’s own preferences for the outcome of the election.

One man had caused riots in London, and overthrown a government at the polls. His name had become famous throughout the country. But the aftermath was anything but a success for Sacheverell and his followers. The Tories fell from power just four years later under the new King, George I, whose preference for the Whigs was obvious to all. The sun would shine on the likes of Walpole, Stanhope and their party for decades to come. Like many modern day celebrities, Sacheverell was unable to live up to his reputation. Fame proved fleeting, relegating him to relative obscurity. Financially he was comfortable and lost nothing of his swagger or flamboyance. It was not uncommon for visitors to be greeted by Sacheverell wearing a ‘gaudy Indian night-gown’.

He died fourteen years after his trial, at the age of 50, probably from the consequences of slipping on an icy step the year before. Later it was discovered that he had been buried next to Sally Salisbury, a high-class prostitute, allowing the Whigs to have the last laugh with verses such as:

Lo! To one grave consigned, of rival fame,

A reverend Doctor and a wanton dame,

Well for the world both did to rest retire

For each, whilst living, set mankind on fire