For the residents of Cairo, the arrival of Mansa Musa, the Midas of Mali, was spectacularly memorable. So ostentatious was the Emperor’s approach that the official responsible for greeting him at the city gates cried: ‘This caravan competes in glittering glory with the African sun itself’.

The sound alone of 60,000 people, and their multitude of animals as they paraded past the city to camp in the shadow of the pyramids must have been cacophonous, even to a city of an estimated half million people.

At the head of the procession were 500 servants, hand-picked by the Mansa, each carrying a golden staff. This established a theme. The watching Egyptians could hardly miss the glistering wealth on display. The nobles who accompanied the King were bedecked in gold jewellery or had strands of the metal woven into their hair or clothes.

Eight thousand soldiers and twelve thousand servants, many wearing colourful silks, followed, and beyond them, ordinary pilgrims and hangers-on made up the bulk of the King’s retinue.

'He caused the price of gold to crash'

Mansa Musa’s 9,000 mile (15,000km) pilgrimage to and from Mecca was among the greatest peaceful events of the Middle Ages. His two-year expedition took him from the Sahel in western Africa up to the Sahara desert, across to Arabia and back. He arrived in Cairo in July of 724 by the Hijri calendar (AD1324).

Peaceful, but not without consequences. During his sojourn in the Egyptian capital, he caused the price of gold to crash, for while King Midas is the richest person in Greek mythology, Mansa Musa is indisputably the wealthiest in the history of the world.

The golden touch

According to the Greeks, Dionysus, the god of wine, granted one wish to Midas as a reward for entertaining the god’s friend and mentor Silenus. The greedy King of Phrygia, in what is now Turkey, asked that anything he touched be turned to gold. He soon realised the double edged nature of his new power. Turning twigs and rocks to gold made him rich. But his wealth was small comfort when his food and his daughter turned to gold. Starving and grief-ridden, he begged Dionysus to lift what had become his curse.

Mythology can be remarkably even handed. In one account, Midas is poor, inheriting only two oxen from his father, Gordius, so his avarice is more understandable. In another he is a wise and benevolent King who discovers a fountain of gold in a barren area of Phrygia, then prays to Dionysus to turn it into water, a more useful resource.

Mansa Musa’s wealth was based on mines in the south and west of his territory – principally around the French colonial town of Bougouni – in the Birimian terranes of the Gold Coast. They are said to have produced a tonne a year, half the world’s supply at the time. Mali remains the third-largest gold producer in Africa today.

But Mali’s annual production was a drop in the ocean. The Mansa’s total wealth is estimated at $400 billion in today’s money. This eclipses the second largest fortune, that of the Rothschild family, by $50 billion. Compared to that, King Midas was an also-ran.

Fooling the nosy

The existence of the Mansa's gold mines was a closely guarded secret, especially from the traders who came from across Africa and the Middle East to do business with the Mansa. To silence the nosy who inquired where his riches came from, the Emperor had a misleading response. His wealth, he said, came from gold plants that grew in ‘a distant corner of my empire’.

You might think that no one would believe such a tall tale. But people can be gullible. Thousands were fooled when the BBC aired a three-minute documentary in its Panorama programme on 1 April 1957 about the spaghetti harvest in Switzerland.

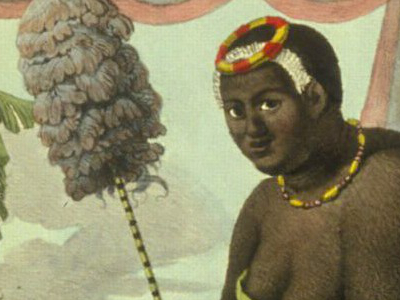

It might be wise to keep the Swiss spaghetti trees, or Orson Welles’s 1938 War of the Worlds broadcasts in mind while reading about the foundation of the Keita dynasty, from which Mansa Musa sprang. A prophecy had foretold that the descendants of Musa’s great-grandfather, Maghan, would achieve greatness, but only if he married the ugliest woman in the tribe. Known as the Buffalo Woman, Sogolon is said to have been hideous. She had a disfiguring hump and, according to the Epic of Sundiata, their son, ‘Her monstrous eyes seemed to have been merely laid on her face.’

Sundiata had a fittingly ignominious start to life. He too was ugly, with a ‘big head’, and was late to start walking. He overcame this disability one day after seeing his mother being ridiculed.

The first step in his military/political rise was winning the chieftainship of his father’s Mandinka tribe, then part of the Empire of Ghana. He went on to subdue his former rulers and turn them into his vassals. His achievements earned him the nickname the ‘Lion King’ of Mali. He was the first to use the title ‘Mansa’, meaning ‘king of kings’, and was Mali’s first Muslim ruler, although he did not force his faith on his subjects.

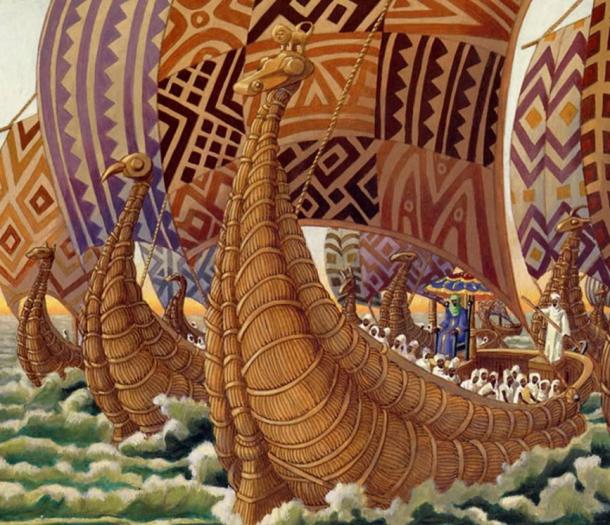

Mansa Musa’s restless need to travel may have been inspired by another ancestor, his uncle and immediate predecessor. Abu Bakr II liked to think of himself as an explorer. He once sent 400 ships to cross the Atlantic just to see what lay beyond. Only one returned. Rather than be put off, the Mansa resolved to lead the next expedition himself. This was even less successful; No ships returned, and the Emperor was never seen again. Musa was proclaimed his successor by default.

The new monarch’s piety was striking. He made Islam the state religion and set about converting more of his people to the faith. Among the potential new Muslims were his gold miners, who until then had practiced traditional African animism – the belief that spirits reside in plants, animals and other natural phenomenon.

The miners were intrinsic to the economy of the Empire. Nuggets they found went straight to the treasury, though the miners were allowed to keep the gold dust and flakes. Gold was so plentiful that one of the largest nuggets was used to tether an imperial donkey.

An imperial pilgrimage

To set an example to his people, and no doubt to inspire further conversions, Mansa Musa decided, twelve years into his reign, to embark on the Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca required of every Muslim who has the means.

Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem are the holy cities of Islam. Medina houses the tomb of Muhammed, but Mecca is where he was born. Pilgrims congregate around the Ka’aba, the cube-shaped building at the centre of the main Mosque, the Al-Masjid al-Haram.

The Kaaba houses al-Hajaru al-Aswad, the sacred black stone, which many think is a meteorite. The Prophet kissed the stone and pilgrims are encouraged to follow his example or point at the rock as they walk around the Kaaba seven times counter clockwise.

The Hajj has been the site of much controversy. Two hundred years after Mansa Musa visited, disaffected Persians were accused of smearing the stone with excrement in order to soil the beards of the devoted. With the onset of the steam age, the Ottoman Empire grasped the commercial benefits of building railways to the site, upsetting traditionalists.

At the time of Mansa Musa’s Hajj, the Middle East was going through a turbulent period, due in part to repeated European crusades to ‘liberate’ the Holy Land. The Ottoman Empire had been founded only a quarter century before the Mansa’s pilgrimage, and when he died thirteen years later, the Hundred Years War between England and France was only just beginning.

The Mansa did not just depart from his capital, Niani. Established tradition required that he deputise his position to the heir apparent. In this case, the Mansa’s son, Maghan, by his wife, Inari Kunate. Surprisingly for a Muslim ruler of the time, there are no other recorded wives or children. Empress Inari accompanied her husband.

Mansa Musa’s large entourage was both a demonstration of his devotion and an act of pragmatic caution. It was better to have all the important governors and officials together with you than allow them to sow dissent at home.

Previous Malian rulers to go on pilgrimage had not fared well. Sakura, a former slave who rose to be one of the Lion King’s generals, briefly usurped the throne after Sundiata’s death. Sakura was killed by Saharan robbers while returning from the Hajj.

City of cones

Niani, the city that Mansa Musa left, has not been definitively identified by archaeologists. But descriptions of it have survived. It was built of conical clay houses with roofs of reed and wood. The palace was a complex of similar buildings surrounded by a high outer wall.

The Mansa must have looked resplendent as he rode away with his retinue of 60,000 to the cheers of those left behind. Amid his finery, he would have worn a notably wide pair of trousers. The girth of lower garments were a mark of high status, but they may also have served as a cushion. He was mounted on a magnificent black stallion, itself bedecked with gold.

'The Emperor's travelling bank account'

The exact size of his caravan is unknown, but in addition to copious supplies to sustain so many people on such a long journey, it included eighty camels bearing nothing but gold. Goblets and jewellery would be given to the worthies he met along the way, while raw nuggets could buy supplies when needed. It was the Emperor’s ‘travelling bank account’, wrote author James Oliver in his 2013 book Mansa Musa and the Empire of Mali.

Cairo was the first major stop, but the Mansa took his time getting there. Frequent side trips allowed him to look at the animals and people of the Malian savannah. Elephants were hunted and their hides turned into drums.

A leisurely beginning

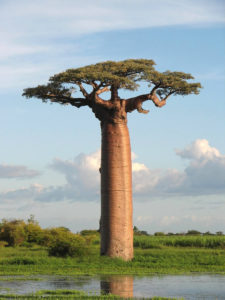

Inevitably they met other pilgrims, including one couple who had chained their children until they had memorised the Qur’an. They also saw one enterprising young weaver who had set up his loom in a hollow baobab tree, affording him shade, shelter, and a fresh breeze when available, without the effort of building anything.

Baobabs are still a common feature in the Malian grasslands as they were when the pilgrimage passed through. Some of them will be the very same trees, since they can live more than 1,000 years. They prefer low lying areas and can grow to almost 25 metres high. With their thick, straight trunks and scraggly tops they look as if they were planted upside down.

One legend claims that they look so strange because the gods uprooted them as a punishment for their arrogance towards other trees. Evil spirits are said to haunt the flowers and anyone who picks one will be killed by a lion. But baobab wood is valuable. It has long been used to make tools, rope, strings for musical instruments, and waterproof hats.

Once they moved beyond the Sahel, this easy terrain was replaced by the desert. Hollywood tends to depict the Sahara as a land covered in wind-blown dunes, but most of it is barren and rocky. The Mansa relied on guides who knew where to find the oases, and how to avoid the dunes.

When the ancient monuments around Cairo eventually came in to view after weeks of hot, meandering travel, it must have felt like deliverance. Most of the pilgrims, like Mansa Musa himself, would only have heard stories about this bustling city. After he set up his camp by the Pyramids, he sent a gift of 50,000 dinars to the Egyptian Sultan, Al-Nasir Muhammad.

The Mamluk dynasty

Egypt was at that time ruled by a dynasty of Mamluks called the Bahri. The Mamluks (the name means ‘owned’) were a relatively new power in North Africa. Their ancestors were slave soldiers from central Asia and Southern Russia. They had seized power during the chaos of the Mongol invasions of Europe, Asia and the Middle East as well as a brief French crusade against Egypt led by Louis IX. Before that, the Mamluk generals had established themselves as powerful military figures who were indispensable to their rulers, the Kurdish Ayyubid dynasty, which had been in Egypt since they were led there by Saladin in the 1170s.

'The Sultan was

already on his

third reign'

The Sultan may have been nervous about the arrival of so many people, thousands of them armed. Mamluk politics had been notoriously cut-throat since the founding of the dynasty. Few rulers died in their beds and the average lifespan for a new Sultan was seven years. One was so terrified of assassination that he always wore a suit of armour. He died of pneumonia.

Al-Nasir Muhammad was already on his third reign, after being twice overthrown. He had, as a result, garnered a ruthless reputation. When he grasped power for the final time, he removed – by drowning, strangulation, starvation, exile and imprisonment – all of his potential rivals. He then appointed loyal Mamluk commanders and encouraged the immigration of new Mamluks who would owe loyalty only to him. His position thus shored-up, Al-Nasir Muhammad decided to risk welcoming his wealthy guest.

As Mansa Musa entered the city, he may have witnessed construction work on the now-famous mosque that bears the Sultan’s name. But he may have had another religious issue on his mind. Initially he had been told that he was expected to kiss the feet of the Egyptian ruler. Seeing this as not only rude but blasphemous, the Mansa refused until a compromise was worked out in which he kissed the ground and praised Allah instead.

This diplomatic move went down well and Al-Nasir Muhammad invited his Malian counterpart and the cream of his entourage to stay at the palace, part of a series of buildings within a complex protected by the high stone walls of the citadel.

During the three months they were in Cairo, the Mansa went on a shopping spree. Egyptian merchants responded by charging five times the normal price, which he happily paid. He even tipped in gold dust. The value of gold plummeted by a quarter and was still artificially low a dozen years later.

He also took up ostentatious philanthropy. He gave away gold ingots to people on the streets. In major cities he visited later, he regularly donated 20,000 ounces (half a tonne) of gold to charity.

After their long sojourn in Cairo, the disruptive guests departed for the remaining thousand miles of their journey to Mecca.

Before he got to the holiest of cities, the Mansa had a brief stopover in Medina. Amid the lavish spending, he did not forget the religious purpose of his progress. Much of the money he spent reportedly went on the construction of dozens of new Mosques -- one was started every Friday.

While in Medina, like many a pilgrim before and after, he visited the tomb of Muhammed and other important sites. He took pleasure in engaging scholars in discussion and debate, finding numerous Imams willing to satisfy his thirst for knowledge.

'The Mansa entered humbly, wearing a plain white robe'

Mecca has many unique laws, including a total ban on non-Muslims entering the city which survives to this day. One may not harm another being in holy city, and sex is banned. Despite his wealth, the Mansa entered humbly, wearing a plain white robe; his wife wore a headscarf of a similar simple design. All ornament was removed.The Mansa participated in the expected ceremonial aspects of the pilgrimage including kissing the Kaaba.

Only men could enter public spaces in the city, which had numerous experts and theologians willing to continue the discussions the emperor had started in Medina. He also furthered his mind on other topics, such as science, mathematics, astronomy and architecture. He attempted to entice many of these academics to come back to Mali with him. The noted architect and Granada native Abu Ishaq Ibrahim Al-Sahili, often called ‘The Moor’ was one particularly important addition to the Mansa’s court. Almost as significant, the Emperor managed to convince four ‘sharafa’ -- descendants of Muhammad – and their families to accompany him on the long journey back to Niani.

Word of rebellion

His stay was cut short by a messenger bringing news that Mali was at war. He had been on pilgrimage for months and communications were not easy, so the news was already old. Mansa Musa wasted no time and ordered the caravan to return. The journey back was not going to be the same stately progress.

The war had broken out between Mali and the Songhay Empire, with their main city of Gao, itself a rich trading centre. Songhay was a strong regional power, stretching almost 1,000 miles across. The cities of Gao and Timbuktu had been incorporated into Mali in 1290 by Mansa Sakura and so was considered a part of the Malian Empire even though it was often in a state of rebellion. Reconquering it was therefore a matter of pride for the Mansa.

'He had finally

run out of gold'

On his way back, he stopped again in Cairo. Astonishingly, he had finally run out of gold, but needed food and supplies for the long journey. The Midas of Mali could not rely on a golden touch to get him out of his financial problems; he had to turn instead to creditors. They obliged, confident they would get their capital back with generous interest of 700 dinar for every 300 lent. Mansa Musa was known to honour his agreements.

His stay in Egypt was brief and there were thousands of miles of desert to cross. But the journey was not without respite. In one instance, Queen Inari complained of the grime of the desert and wished for a river where she could bathe. The Mansa ordered that a thousand foot long trench be dug and lined with stone and wood. Meanwhile, thousands of servants went to fetch water from the nearest oasis, so that his wife and five hundred of her women could bathe.

With sixty thousand people, most on foot, the return journey was slow, allowing the course of the war to turn. The Emperor’s most talented general, Sagmandia, had recaptured Gao and Timbuktu, re-incorporating them into the empire. This changed the Mansa’s plans and he abruptly turned south towards the captured city so he could take the surrender of the Songhay king, Dia Assibai, in person.

When he entered the city he took the King’s statement of submission, annexing all the lands previously claimed by Songhay. The King’s two sons, Ali Kolen and Sulayman Nar, were taken as hostages, to be employed as officers in the Malian army. Many of the other captured Songhay were forced into servitude, mostly in Mali’s mines, helping to extract the gold and salt that was the bedrock of the empire's wealth.

The Mansa toured both Gao and Timbuktu. Although delighted by their commercial potential and their position on major trade routes, he was dismayed by the state of their mosques. Even if many of the elite had converted to Islam, the Songhay people remained lukewarm towards the religion. He asked his friend Al-Sahili, The Moor, to build a new Mosque in each city.

The mosque in Timbuktu in particular would become famous as an example of the Malian style of architecture. Like those in the capital, it was built with sun-dried mud, but unlike those in Niani, it was square not round. It has conical minarets rather than domes, with flat roofs, arches, and exposed timbers, called toron, on which craftsmen could climb as they carried out repairs. The walls are an earthen terracotta colour which glows impressively in the setting sun.

The Moor also erected the Djinguereber mosque in Timbuktu and a smaller mosque that was to become the University of Sankore by the end of the Mansa's reign. Fully staffed with Islamic scholars, this was to be a noted seat of learning in West Africa, with 25,000 students and a library that housed 400,000 to 700,000 manuscripts. That made it the largest on the continent since Julius Caesar burned down the great Library of Alexandria in 48BC. Lessons at the University were conducted in Arabic, the language of scholars in the Middle East and North Africa.

Home in style

After his tour of Timbuktu, the Mansa decided to return to his capital in style. He commissioned several barges so that he, Inari, the other women and his prized descendants of Muhammad, could travel to Niani by water. The rest of the Caravan would have to make it there by land.

Huge cheering crowds with banners greeted the returning hero; a carnival atmosphere was in the air. He spoke with his son Maghan and the other governors whom he had left to rule in his stead. He judged his son a weak leader and any thoughts of returning to Mecca to live out his retirement were shelved. This evaluation proved correct; his Empire unravelled within decades of his death. One of Maghan’s first mistakes was to grant Goa’s hostage princes greater freedom of movement. Eventually they escaped from Maghan’s court and helped Goa become independent again. Maghan was succeeded by his uncle, Mansa Musa’s brother, Sulayman; he would spend his reign trying to keep the empire together, at which he was more successful.

Mansa Musa never again left the Empire. In his later years he would become a strong patron of the sciences and arts, building on what he had learnt in Mecca. Book traders in particular did well out of the Emperor’s desire to gain as many manuscripts as possible. His legacy as a great builder, with the rich architecture of ‘The Moor’ would also be cemented during his later years. Cultural and diplomatic ties flourished with other Muslim powers, most notably Egypt.

Despite this increased engagement with the outside world, much of Mali remained shrouded in mystery, especially its ‘gold harvest’. To many, the spectacular displays of wealth made during his pilgrimage were their first introduction to this mysterious empire. Mansa Musa’s control of the gold trade and his ability to make or break markets gave him a god-like aura. However, as James Oliver concludes, ‘gold alone did not lift Mali into its Golden Age’, it took an individual of extraordinary ability.