On Lemuel Gulliver’s second voyage, as told in Jonathan’s Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, he is abandoned by his crewmates in the extraordinary land of Brobdingnag, where the trees are so tall he could 'make no computation of their altitude' and it took him an hour to walk across an otherwise ordinary field.

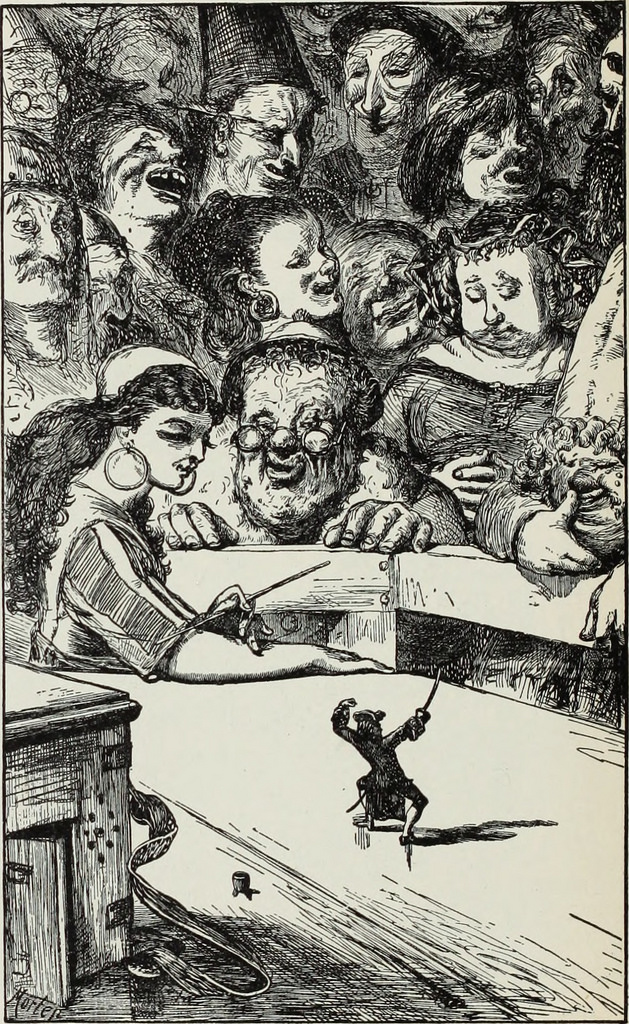

The inhabitants are similarly proportioned – 'tall as an ordinary spire steeple', he notes. Even a dog has the mass 'of four elephants'. Gulliver is eventually found by a farmer, who exhibits him for profit. Despite this demeaning experience, the traveller finds some crumbs of comfort. He strikes up a friendship with the farmer’s nine-year-old daughter, whom he calls Glummdalclich – which means little nurse in the giants’ language – because she was small for her age, 'not above forty feet high'.

It is not long before the story of Grildrig, as Gulliver is known, reaches the ears of the royal court. Eventually the greedy farmer, who thinks Gulliver is about to die, sells him into imperial service. Glummdalclich also goes to court to oversee his welfare.

His new master and mistress are the King and Queen of Brobdingnag. At first the King does not believe Gulliver is real, thinking him a “piece of clock-work”, and gets scholars to conclude that Gulliver could not be a result of “the regular laws of nature”. The queen is delighted by her charming and witty new servant. She commissions a box for Gulliver to live in, which despite being luxurious, is little more than a glorified dolls house.

Gulliver’s Travels was written in 1726 during a time of relative peace in Europe, the colony of Georgia was yet to be founded and the edges of the map were still not fully coloured in. Indeed, Swift placed Brobdingnag on the unexplored western coast of North America. Readers ate it up.

The book also had another purpose, for the contemporary political situation in Britain was anything but peaceful. The country had gone through its first major financial crash six years earlier when the South Sea Bubble popped and Robert Walpole had emerged as the first de facto Prime Minister.

Swift, an Anglo-Irish clergyman well known as a wit and satirist, had written both for and against the government of the day for decades. He was part of a group of writers engaged in literary warfare against Walpole’s new regime, and Gulliver’s Travels was squarely aimed at the corruption he saw in the heart of British politics.

The story of a land of giants may not have seemed fantastical to some of Swift’s readers. Before people read the fictional account of a giant King treating Gulliver as a curio, reports had circulated of a real-world monarch who was combing Europe for extraordinarily tall men to entice into a regiment of giants.

Short and squat with bulbous eyes

Unlike the King of Brobdingnag and the marching colossi in his army, Frederick William I of Prussia was as far from a giant as you could get. At 5’5”, he was relatively short and squat with bulbous eyes beneath a high forehead. People found him intimidating, though, an effect that he tried to accentuate by smearing bacon fat on his face. Frederick William also had a legendary temper made worse by frequent bouts of porphyria, the same illness that afflicted his relative, King George III of Britain. Frederick William would thrash his own officers and even passers-by with his cane and had two pistols filled with salt to take occasional pot shots at servants. It was said that one of his staff had dropped dead on the spot after hearing that he had an audience with the King of the Giants.

The King’s notorious temper was at its worst when combined with his remarkable memory. He was able to identify an ordinary drummer, who had deserted to the Polish army during a state visit, in a crowd of ordinary citizens. He was even able to recall the man’s name and the company he deserted from. The drummer was duly punished.

'All learned men

are fools'

Frederick William was 38 and had been collecting giants for more than two decades when Gulliver’s Travels was translated into German, a year after it came out in English, but he almost certainly never read it. He was famous for being a complete Philistine who despised all forms of literature and learning that were not martial in nature. Whereas the Brobdingnagian King was described as ‘learned’ in philosophy and mathematics, one of the favourite expressions of the Prussian King was ‘all learned men are fools’. When he caught his son reading, the King would throw the offending book in the fire.

Coarse and bawdy practical jokes were more his style. He would play these on his cronies while smoking and drinking healthy measures of beer at his infamous ‘Tobacco Parliaments’, in effect a private members’ club for the King’s friends. His favourite fall-guy was Jakob Gundling, the president of the Berlin Academy of Science who specialised in polygraphy, devices for writing in duplicate. Gundling would be honoured one day and humiliated on another. After being made a baron, he was forced to sit beside an ape dressed to look like him. The King and his court also revelled in defenestrating the unfortunate scientist into the moat. This inspired some of the giants, who tried a similar trick from the drawbridge, in winter. Tying a cord to the hapless Gundling the soldiers repeatedly pulled him up and down until he broke through the ice. A prank that was later recreated for the King's amusement.

Even one of his closest confidants, Count Seckendorf, was forced to smuggle books into the castle at Wusterhausen and hide them from the King so as not to lose royal favour. Seckendorf, the Holy Roman Empire’s Ambassador to Prussia, had earned the trust of the King over many years. As young men they served together on campaigns in the Netherlands, and kept up a regular correspondence when the Count was away from Berlin. Seckendorf often sent the King gifts of rare delicacies for his table and tall men for his regiment, the Potsdam Giants.

An austere castle, devoid of ornamentation

The castle of Wusterhausen was probably where Frederick William first discovered his obsession with giant warriors. It would later become one of his favourite residences. Primarily used for hunting in the autumn, the castle was like the King – austere and devoid of ornamentation.

When his father, Frederick I, allowed him command of his own unit there, the young Frederick William apparently spent his allowance to replace short soldiers with tall peasants, whom he would then drill. Fearing his father, the Prince would hide his rustic recruits in lofts and barns when the King came to visit. These early exercises were a harbinger of things to come. Frederick I did not share his son’s passion for giants but had given him an important legacy, for Frederick had used his influence with the Holy Roman Emperor to become the first King of Prussia.

Just over a decade before the publication of Gulliver’s Travels, Frederick William ascended the throne of Prussia as ruler of a confident new kingdom, one which he could shape in his own image. He had the power to indulge his passions and one of his first acts was to create his regiment of Potsdam Giant Guards. The King himself was colonel of this force of ‘Great Grenadiers’ who were soon given the nickname Lange Kerls (Long Guys). These towering soldiers drew curious visitors from across Europe all eager to gaze at the King of Prussia’s pride and joy.

Their uniforms consisted of a gold-lined blue jacket over straw coloured waistcoat and breeches, leading to another nickname, the ‘Blue Boys’, coined by the King himself. Frederick William directed that they be made to look even taller with a red mitre that added twelve or fifteen extra inches. Neither skill nor experience were needed to qualify for the regiment, only height. Recruits had to be at least six foot, and many were much taller, with the largest nearing eight foot. It was an indictment of the King’s bias that talented but short officers would often be denied promotion.

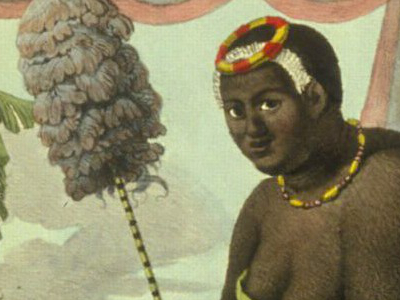

Few foreign courts treated the Potsdam giants as anything other than figures of curiosity or ridicule. Their fighting quality was considered poor, with visitors commenting on the ill-proportioned nature of many of the recruits, being ‘ugly’ or ‘bow-legged’. Several also seem to have had mental deficiencies. It mattered little as the regiment remained purely ornamental, never to be risked on the battlefield. They were instead given ceremonial duties. These included marching with their hands linked across the top of the royal carriage. When the king was ill, he would command that two hundred of the tallest men march past his bed to make himself feel better, preceded by ‘tall-turbaned Moors with cymbals and trumpets’ and their mascot, ‘an enormous bear’.

‘not a country

with an army

but an army

with a country’

Despite his angry and belligerent attitude and his interest in all things martial, Frederick William’s reign was one of the most peaceful in Prussian history. His foreign policy was almost exclusively influenced by his desire for giants. But his reforms laid the foundations of the German Empire that would rise over a century later. His parsimony swelled the royal coffers, and hence the army. During his reign it would become the fourth largest in Europe, despite Prussia ranking only tenth in territory and twelfth in population. His son, the future Frederick the Great, owed his later military success to his father’s reforms. So imposing did his army become that Prussia was later described as ‘not a country with an army but an army with a country’.

This military expansion included the Potsdam Giants. What started off as 1,200 men eventually grew to 3,000. He obsessively combed his own lands and then Europe for recruits. “The most beautiful girl or woman in the world would be a matter of indifference to me, [but] tall soldiers - they are my weakness”. It didn’t take long for the powers of Europe to exploit his passion diplomatically.

A giant for a flautist

The Russians caught on early. A year after Frederick William ascended the throne they sent giant recruits to Berlin to curry favour. An Austrian diplomat claimed that promising giants to Frederick William was a surer way to gain a diplomatic triumph than ‘the most powerful arguments’. It was also said that Britain convinced Prussia to sign at least one disadvantageous agreement by promising 15 tall Irishmen, a gift seen as greater than “many first-rate men-o’-war”.

Word travelled far and fast. Newspapers reported members of the “Gigantick Grenadiers” coming from as far afield as Persia. Closer to home, a Saxon field marshal swapped a giant for an accomplished flute player, while Count von Wackerbarth, another Saxon, traded 30 giants for a particularly fine Spanish Stallion.

The King’s mania carried a hefty price tag. In almost everything else his stinginess was legendary. During his reign the phrase “working for the King of Prussia” became a byword for earning a small wage.

But the normally economical monarch would pay almost anything to bolster the regiment. By the time of his death, the hobby had cost the King 700,000 thaler, roughly £200m today. Much of this ended up in private pockets. An Austrian noble once sold his son for a small fortune and a pension from the Prussian purse.

Another expense was the network of agents the King established across the continent, encouraged by a bounty that varied with the height of the recruits. The agents were instructed to use any means necessary, including the false claim that the giants would regain their liberty after a short enlistment. But once they were in his service, Frederick William would never let them go. As a result of this subterfuge, the Prussians gained a reputation for not keeping their agreements with recruits.

So generous were the bounties that when manipulation and bribery failed, outright coercion and kidnapping were often tried. Agents were known to break into monasteries to carry off monks at prayer and in one instance a Dutch clergyman was taken away in the middle of his sermon, along with four members of the congregation. In another incident a particularly lanky carpenter was convinced to lie down in a box of his own making. It was quickly boarded up and sent to Berlin, with the poor artisan inside. The recruiters, though, failed to drill air holes, and he suffocated. Nor did the agents respect rank; anyone was in danger, including a particularly tall Austrian diplomat seized in Hanover.

Often these impressments were carried out with the connivance of the local Prussian diplomats. One notorious example was Berlin’s Ambassador to London, Caspar William von Borcke. Coming from an old aristocratic dynasty, Von Borcke had held diplomatic postings in several European courts. His appreciation of culture and science marked him as different from his master. He was the first to translate a full-length Shakespearean tragedy into German. His Julius Caesar was an attempt to popularise and champion the work of the Bard among the German public. However, it was his enlistment of 'Long Guys' that earned him the anger of Shakespeare’s countrymen; on his dismissal, he was denied the traditional farewell audience with the British monarch, George II.

Von Borcke had arrived in London eight years after the publication of Gulliver’s Travels. The city would have been very different from today. St Paul’s was newly built, the streets were filthy and the housing poor. Many of its inhabitants were addicted to the new craze for gin, catered to by an estimated 7,000 gin shops in the capital.

It was here that Von Borcke became notorious for impressing British Brobdingnagians. One of the most famous to draw the ambassador’s attention was the Irishman James Kirkland. At around 7ft tall, he was hardly an inconspicuous figure. He would have been an impressive sight for the throngs of Londoners, most of whom would have barely reached his shoulder; the average height for a man was less than 5’6”.

Kirkland probably felt honoured when the German diplomat offered him employment as a footman. However, after the Irishman willingly accompanied his new master on board a ship in Portsmouth, things turned rough. Perhaps Kirkland got cold feet, for he was set upon by a group of men who bound and gagged him for transportation to Berlin.

Another of Von Borcke’s unsuspecting targets was 6’4” William Willis, whom the ambassador employed as a ‘valet’ for a fictitious Irish Lord. With an annual wage of £20, plus 14 shillings a week for board, the offer was too good to refuse. Before long he was in Potsdam, having his measurements taken for a new uniform.

Potsdam would have been quite a shock for Kirkland and Willis. It was tiny compared to London, although Frederick William’s activities would increase the civilian population from 1,500 to 12,000 during his reign. It was only 18 miles from Berlin but the King considered it “the heart of the military monarchy”. Frederick William had pulled down the old town to make way for a new residential district and ordered that each family living there had to billet between two and six soldiers in their lofts. The King even hosted some giants in his palace as an example. Almost everyone in Potsdam had a connection to the military, and even three decades after Frederick William’s death, soldiers made up nearly half the inhabitants.

At the heart of the military monarchy

Frederick William’s study in the Palace at Potsdam, his working residence, overlooked the parade ground so he could watch his Blue Boys drilling. Portraits of his soldiers, painted by the King himself, often from memory, still decorate his residences. When one particular favourite died, the King had his likeness rendered in marble.

His living quarters at Potsdam were notoriously Spartan. When he came to the throne, Frederick William stripped the royal palaces, selling off most of the valuable plate and furniture accumulated by his father. He even had the former king’s collection of medals and the silver handles from his carriages sent to the mint.

The daily drills could go on for hours and most found life in the Great Grenadiers hard. The King was a passionate believer in the benefits of medical practices that would today be considered quackery. He insisted, for example, that his grenadiers be bled regularly. As with everything else, the King set an example.

But for those who went along willingly, life could be good. They would have been greeted personally by a monarch with “tears of joy” in his eyes. To be a member of the Potsdam Giants meant having an intimate relationship with the King, who knew all of their names. All recruits received the best care and a new uniform every year.

To make them feel appreciated, the King resorted to outright bribery, giving some of his favourites lands and sinecures. Many were allowed to carry on a trade. As a result of their privileged status, the giants were often above the law. In one instance, Fredrick William caned a whole military tribunal for condemning one of his “Blue Boys” to death for theft. It became a common trick for lawyers to petition on behalf of their clients through a Great Grenadier knowing that the King would find it impossible to refuse.

Unable to condemn

them to death,

Frederick William had

the ringleaders’ noses

and ears cut off

However, outright dissent was not tolerated. Unlike Gulliver, those forcibly impressed soon realised they could never leave the Prussian land of the giants. Upon arrival, all members of the giant grenadiers had to swear fidelity to the King. For those who refused, the punishment could be bloody. William Willis and another Englishman, John Evans, were beaten so badly after refusing the oath they had to take to their beds for several days.

Great Grenadiers who found the regime oppressive sometimes resorted to mutiny and desertion. One failed attempt involved 87 Hungarians, Poles and Wallachians who planned to burn down Potsdam and escape in the confusion. Another group of 14 giants who plotted escape were betrayed by one of their number.

Escapees paid with their noses and ears

Although heartbroken, Frederick William could not find it in his heart to condemn them to death, instead he had the ringleaders’ noses and ears cut off. The same fate awaited a dozen Great Grenadiers who planned to cut the throats of their guards and make a run for it. As well as the mutilation of their faces, they had to run a gauntlet thirty-six times. Their leader, meanwhile, was “pinched with burning hot pincers” and later hanged.

Some giants resorted to less violent means of escape. Nineteen Englishmen, among them William Willis, wrote a petition to the British authorities, asking them to intercede on their behalf and release them from their “Cruel Bondage”. Their efforts were in vain. Frederick William would never part with one of his precious giants. The British Ambassador to Prussia, Guy Dickens, wrote after an attempt to secure Willis’s freedom that “I should be less unreasonable if I demanded a province or two … Release! They have no such word in their dictionary”.

It was not unheard of though for one of the King’s “Blue Boys” to escape. Around 250 managed to flee their torment each year, although hunting parties were sent after them. Dr Robert Ergang in The Potsdam Fuhrer claims that when Frederick William heard the news that he had lost a giant his “good humour would vanish for days”. The usually garrulous monarch said nothing for an entire evening once, upon hearing of a Bohemian’s desertion.

A steady stream of fresh recruits was needed to compensate for those lost to death or dissertation. And the agents who were so well rewarded when they succeeded, would also be punished if they failed. In one instance a major was sent to prison for six years because he had no new tall recruits to present to the King. Later in his reign, two more majors were “broken like a glass” in front of their companies. Prussian officers in general were “not sure of their bread” unless they showed up with giants. A British diplomat claimed that many of these officers longed for a war simply to cure Frederick William of his addiction.

Bizarre experiments

In an attempt to make his giants even taller, the King resorted to a series of bizarre pseudo-scientific experiments. His cruelties included a specially constructed rack, where soldiers would be stretched. It was said he would personally supervise these sessions while eating his lunch.

After these experiments failed, Frederick William turned instead to a crude form of eugenics, a science made infamous by the Nazis two hundred years later. Like an eighteenth century horse breeder, the King sought out women of a similar stature to his “Long Guys” and married them to each other, in the hope that their children would be giants too.

In one memorable instance, he spotted a tall woman outside the capital and gave her a message to be delivered to the commandant in Berlin which said “The bearer is to be married without delay to Macdoll, the big Irishman”. The woman, who was from Saxony, seems to have been able to read, for an old crone was the one who eventually delivered the message. Macdoll’s shot-gun marriage was followed by a hasty annulment, not because of his wife’s age and looks, but because the king thought her too short.

The King took a keen interest in the children of these unions. He had to be dissuaded from attending one birth during impassable winter conditions, but come spring he demanded to see it immediately. ‘Make Haste!’ he ordered, ‘The weather is good now.’ According to Dr Ergang, Frederick William was particularly pleased when he was chosen as godfather for any babies that did emerge.

The King was not above bending the rules of diplomacy to get what he wanted. He refused to extradite a Captain Pretorius to Denmark for the alleged murder of Count De Rantzau unless the Danish authorities delivered seven tall men for his army. Apparently only three of the required stature could be found in Denmark itself, forcing Frederick IV to send a scout to Germany to find four more to make up the shortfall.

The Prussian monarch once granted asylum to the Bishop of Vilna (now Vilnus, Lithuania) in return for a number of tall recruits. The cleric must have realised the King wasn’t joking when he was detained until the debt of giants was paid.

In the most extreme example of Prussia’s neglect for the norms of international relations, Frederick William almost went to war with his cousin George II of Britain over the enlisting and kidnapping of tall men from his territories in Hannover. George believed Frederick William had refused to punish the recruiters enough.

The cousins had a longstanding feud that stemmed from their childhood, made worse by George marrying Frederick William’s first love, Caroline of Ansbach. And the Prussian took it with him to the grave. George was the only enemy that Frederick-William refused to forgive on his death bed.

Luckily, the recruitment dispute went no further. Fearing a German civil war within the Holy Roman Empire, of which Prussia and Hannover were both member states, the Emperor and other powers managed to nip the problem in the bud through a congress held at Brunswick.

But there were other diplomatic obstacles. The Holy Roman Emperor, Charles VI, rescinded his earlier decree allowing Frederick William free-rein to recruit in the Imperial dominions. A year before the Prussian King’s death, the vice-governor of Riga published a “very rigorous decree” against the foreign enlistment of tall men.

'Had I been treated

so by my own father,

I would blow my

brains out'

By then, his heir had decided that humouring his eccentric father was the surest way to an easy life and smooth succession. Like many of his fellow subjects, or tall men in neighbouring countries, the future Frederick the Great had lived in constant fear of his father’s tyranny. A cultured intellectual, who would later be friends with Voltaire, Frederick was very much the opposite of his father. This was despite the efforts of Frederick William, who prescribed every hour of Frederick’s day through a rigid syllabus and routine. The schedule covered when the Prince should wash, eat, and enjoy recreation.

The humiliation of Frederick

The Prince also endured constant beatings and humiliations, the King’s cane being the usual instrument of punishment for even the most trivial transgressions. Frederick was once caned because he chose to use a three-pronged silver fork rather than one with two tines, which Frederick William deemed a sign of effeminacy. On a visit to Saxony, Frederick was thrashed and dragged across the ground by the hair in full public view. Frederick Williams’ response to these tortures was to goad his son further by saying 'Had I been treated so by my own father, I would blow my brains out'.

Frederick had attempted to escape his overbearing parent just once, by fleeing to Britain, only to be captured and nearly executed on Frederick William’s orders. In a rare show of compassion the King instead decided that his son’s accomplice and possible lover, Hans Hermann Von Katte, should be the one executed, reportedly sending some of his grenadiers to force Prince Frederick’s head through the window of his cell to make sure he watched his friend’s execution.

The Crown Prince would later use his father’s mania for tall soldiers to his advantage. He deflected questions about his lack of religion by finding giants to please the King. By the late 1730s, he even employed his own agent for this purpose.

In Frederick William’s twilight years, the Potsdam giants had become both an object of fear and mockery by his own subjects. He and his army of agents were used as bogeymen by Prussian mothers, admonishing their sons to 'stop growing or the recruitings will get you'. In a move that would probably have delighted the author of Gulliver’s Travels, a domestic satire was produced that imagined the King’s agents going down to the underworld in order to kidnap the biblical giant Goliath for his army, forcing the Philistine to flee to St Peter for sanctuary. Frederick William was according to London’s General Evening Post in a “terrible fury” over the production of this lampoon and ordered a “strict search” for the culprit.

Reports of what the King said to his son about the Giants, while he lay dying in 1740, are conflicting. Dr Johnson, author of the first English dictionary, said Frederick William asked the Crown Prince to perpetuate the regiment, but his son was non-committal. Dr Ergang and others relate a different story, in which shortly before his death the King owned up to the folly of his mania, and expressed the hope that his son would act more wisely.

In the end, Frederick the Great disbanded the regiment, saving enough to establish four new ones. His army would go on to be one of the most feared and admired in Europe, adding the rich province of Silesia to the kingdom and defeating many of its larger rivals, including the Austrians and French.

What became of the giants after their release is not clear. Many were likely relieved by the King’s death and simply returned home. Others, like the Irishman James Kirkland, stayed put, reportedly going into business.