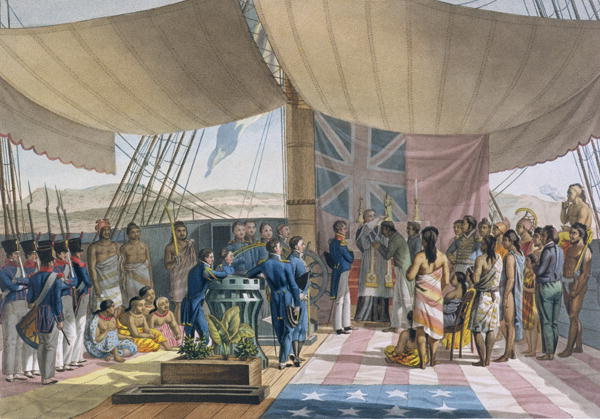

The heir to the throne of the Sandwich Islands presented a dignified but odd sight as he strode along the shore towards the nobles who would pronounce him king. Beneath the traditional feather cloak he wore the crimson jacket of an English soldier. And his 'princely hat' was a plumed bicorn, not unlike that of Admiral Horatio Nelson. Behind Liholiho, two chiefs carried Kahiili, feathered standards that indicated his royal rank. But his honour guard bore muskets rather than the traditional spears. Forty years after their ‘discovery’ by Captain James Cook, the Hawaiian islands were in the middle of a cultural revolution.

While the upheaval was inspired by outsiders, it was directed by the local woman who stepped forward to block the soon-to-be monarch and his entourage. She was an imposing sight. Hawaiians regarded big as beautiful, and at almost five hundred pounds (220kg), she was arguably the most attractive woman on the islands.

‘Behold these chiefs and the men of your father, and these your guns, and this your land,’ she said. ‘But you and I shall rule together’.

Liholiho seemed unperturbed by this bare-faced grab for his power. He might have ordered some terrible retribution on the woman, but instead he mildly assented and was duly acclaimed King Kamehameha II.

The woman was neither the new King’s wife nor his mother but his stepmother, and as such had no claim to authority except what she wielded by force of personality. Her name was Kaahumanu and her long shadow still stretches across Hawaiian history.

Her husband, Liholiho’s father and regnal namesake, Kamehameha, (translation: ‘The Loneliness of a God’) was the first king of a united Hawaii. 'The Conqueror', as he was also known, had forged his Kingdom of eight islands through the bloody subjugation of four rival chieftains.

When Kamehameha died in 1819, George III was still on the throne of the United Kingdom, though his twilight years had sapped the last vestiges of his sanity. The founding of the United States was within living memory and the battle of Waterloo had been fought just four years earlier.

Liholiho’s investiture as the second sovereign was suitably grand. But despite the pomp and ceremony, many must have felt the recent death of Kamehameha was the end of an era. His reign would be almost impossible to live up to, let alone surpass. They had yet to reckon with Kaahumanu.

A fit mate for a warrior king

She had been 16 when Kamehameha made her his eleventh wife. But she was his favourite from then until his death 34 years later. Since the Conqueror took another 19 brides, the favour he showed her was all the more exceptional.

Her huge size was often commented upon, particularly by westerners. Laura Judd, the wife of an American physician and missionary, said Kaahumanu treated them like pet children. 'She could dangle any of us in her lap, as she would a little child, which she often takes the liberty of doing'.

But the Queen’s intellect and her skill as a politician were equally impressive, as her intervention in the investiture demonstrated. Kaahumanu was, according to the historian Manley Hopkins, 'beloved for her own sake' and a woman of 'remarkable character' who made a 'fit mate for a warrior king'. Kaahumanu and Kamehameha were a team, one whose bonds were strengthened by the seismic events that shaped the new kingdom’s early history.

Where no land should be

It is easy to forget that Cook only chanced upon Hawaii in 1778, the year France joined the American Revolutionary war. He immediately grasped the strategic implications of the archipelago’s location. The islands are almost 7,000 km (4,000 miles) from the nearest continent, making them a convenient way-station for anyone crossing the Pacific.

Their very existence is odd. Volcanos are typically found where tectonic plates meet, such as the Ring of Fire that causes eruptions and earthquakes from Krakatoa to San Andreas. But Hawaii is in the middle of the Pacific plate, where it slowly passes over a subterranean hot spot, leaving behind a chain of huge, extinct volcanos. Measured from its underwater base to its tip, Mauna Kea is over 10.2km high, compared to Everest’s 8.8km.

Charles Darwin would have loved Hawaii. As with the Galapagos, isolation has turned Hawaii’s eight islands and 124 islets into an evolutionary hothouse. No reptiles and hardly any mammals, reached the archipelago, but those creatures that did have radiated to fill a myriad environmental niches. And because of the volcanic mounts at the centre of the islands, these range in climate from tropical to Alpine.

Take, for instance, the Hawaiian honeycreepers. While Darwin’s Galapagos finches have evolved into 14 species, the honeycreepers branched into at least 56, with a wide variety of colours and beaks. That of the multi-coloured ’akiapola’au has been compared to a Swiss Army knife – because the upper and lower jaws are so different. Curved and slender on top, thick and straight below, it is ideal for digging insects from beneath tree bark.

Insects too have expanded into more than 5,000 unique species, even though some families, such as ants and cockroaches, are completely absent. A quarter of the world’s Drosophilidae, the family that includes fruit flies, are found on the islands.

While many of these variations involve changes to diet, the most drastic occurred in caterpillars of some species of Eupithecia, or pug moth. These have become carnivores, equipped with raptor-like claws for snatching passing flies out of the air.

The arrival of humans between AD300 and 600, caused the predictable fall in biodivesity, not least because of the dogs, pigs, and rats they brought with them from the Marquesas islands 4,000km to the south. Since Cook’s arrival, extinctions have accelerated. Only 18 species of honeycreeper are thought to be left.

To the later annoyance of the inhabitants, Cook named their tropical home the “Sandwich Islands” in honour of John Montague, the 4th Earl of Sandwich. Montague was the First Lord of the Admiralty at the time, and thus Cook’s superior. An early champion of cricket, he is best known as the supposed inventor of the culinary sandwich, a convenient meal when he didn’t want to leave his desk, or the gaming tables.

The return of the god Lono

The first islanders to greet Cook and his crew lived on the shore of Kealakekua Bay on the Big Island of Hawaii. HMS Resolution dwarfed the largest of their canoes, let alone their surf boards. It was 110ft long and displaced 462 tons. Its deck towered above the waves, and the masts stretched to the sky. The intricate rigging must have seemed incomprehensible. But what really caught their attention was the unimaginable wealth she bore in the form of iron.

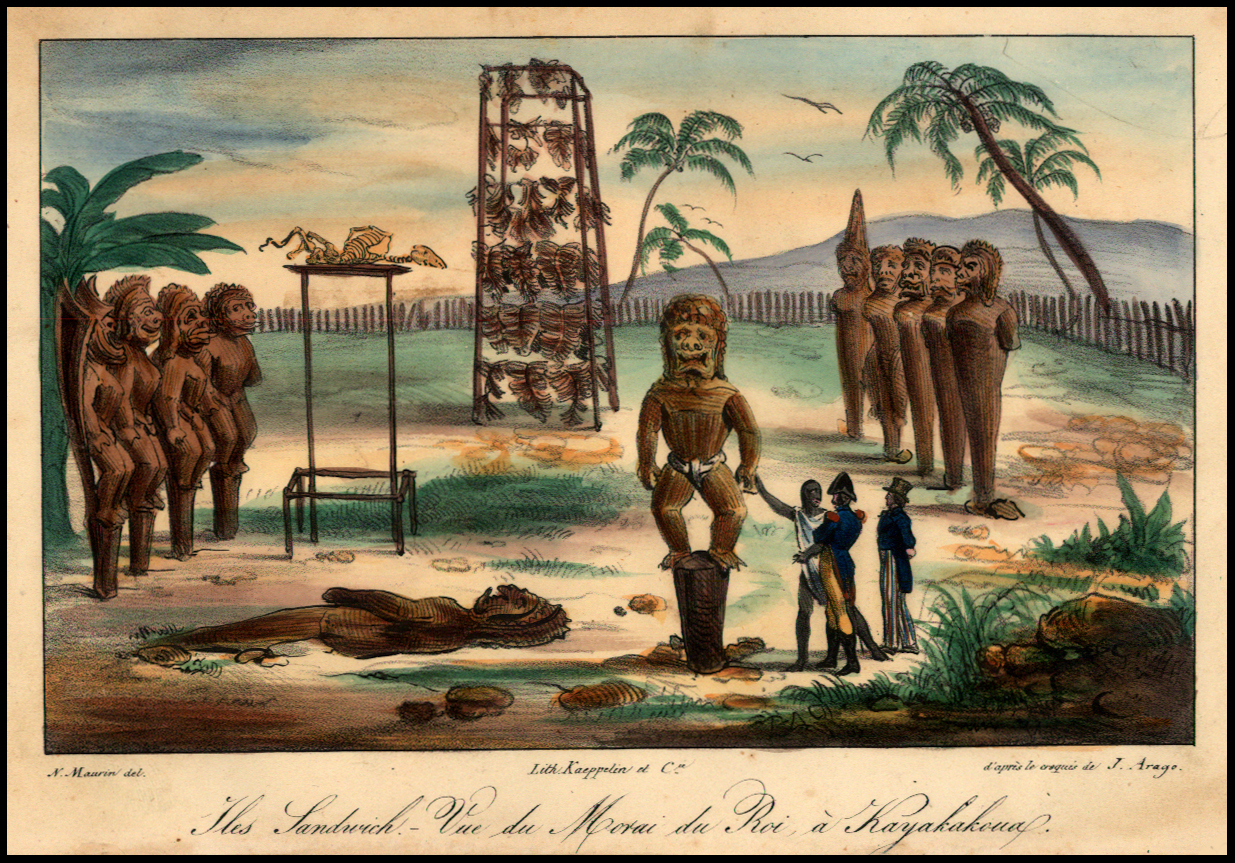

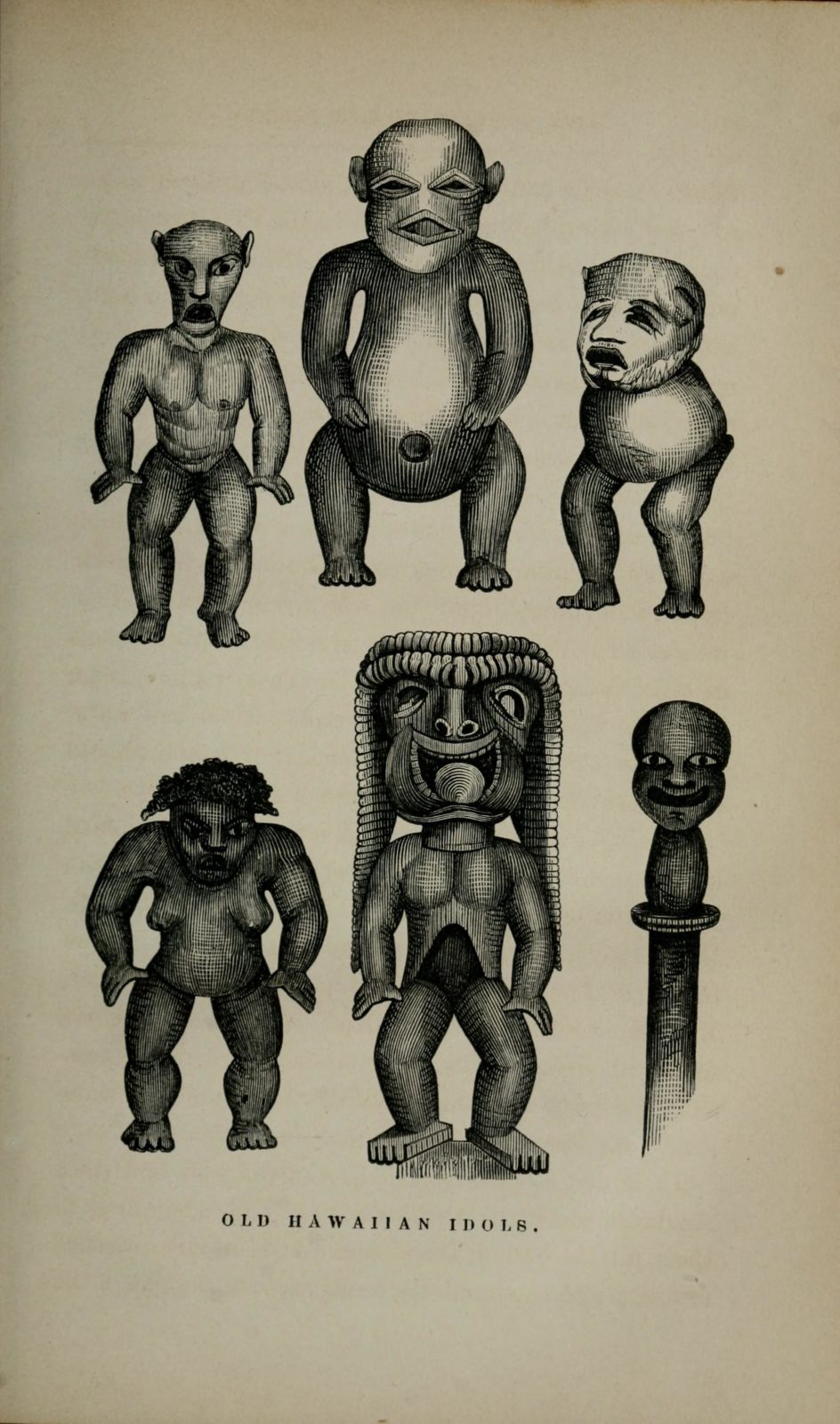

Their village comprised scores of grass houses, or hale – each a wooden frame covered with a thatch of sweet-smelling pili grass. Hawaiians spent most of their time in the open, so they had little call for elaborate homes. Numerous ki’i idols, the largest carved from the ohi’a-lehua tree that grew high on Mauna Kea’s slopes, stood between the houses. Further inland were white oracle towers, also made of ohi’a, which priests climbed in search of divine prophesy.

The strange newcomers did not fit easily in to Hawaiian society, which was strictly divided into the ali’i, or noble class, and the maka ainana, the common people. The ‘purest’ bloodlines were encouraged to intermarry – even siblings – so the ali’i looked like a separate race, towering above the commoners they ruled. This desire for purity was linked to the concept of mana, the source of spiritual power. In the Hawaiian religion, mana was hereditary, though it could be enhanced by killing one’s enemies in battle and owning their remains.

"The women were

eager to make love

to a god and his crew"

At Kealakekua, the islanders were in the middle of festivities celebrating Lono, the god of storms, harvests and fertility, when Cook made land. Legend said Lono had sailed away from Hawaii after killing his lover, whom he suspected of infidelity. Cook’s arrival in a magnificent vessel seemed to fulfil the prophesied return of the deity.

The welcome given to the strangers was rapturous. The women of Kealakekua were particularly eager to make love to a god and his crew. According to American author James Haley, they engaged in 'mass mating' with Cook’s men, who after months at sea were no doubt happy to oblige.

During this sojourn, a young Kamehameha was among those who boarded Resolution. The nephew of King Kalaniopu’u was astonished by the power of the foreigners’ weapons. Hawaii had no natural source of iron, an almost legendary material that occasionally washed up on shore.

Cook left after eighteen days, but a storm drove him back to the bay with a broken mast. This sign of vulnerability caused the islanders to doubt his divinity. When they refused to return one of Resolution’s boats, the captain hatched the plot that would cost him his life. Going ashore, he invited Kalaniopu’u to return with him to the ship, thinking to ransom him for the tender.

"Captain Cook was

baked in an oven,

but not eaten"

But a scuffle broke out on the beach, during which Cook was beaten and fatally stabbed in the neck. The islanders killed four other sailors in the landing party and wounded two. Cannon fire from the departing British ship injured several on shore, including Kamehameha, hardening his ambition to obtain such weapons for himself.

After the skirmish, Kalaniopu’u had the captain baked in an oven, though not eaten, as is often believed. Cooking removed the flesh from his bones, which were preserved for their mana. Unlike some Pacific islanders, the Hawaiians were not cannibals, though human sacrifice was an integral part of their culture.

Kamehameha’s indoctrination had begun with a rite that was only somewhat less barbaric. Like others of his class, he was tested at birth by being placed on a three-and-a-half-ton block of lava called the Naha stone. If he cried, he would be condemned to live as a commoner. He did not, and so was deemed a true ali’i.

As a young man (some accounts say he was just 14) he returned to the stone. One legend said that the man who could move the Naha stone would unify the islands. When he arrived at the temple of Pinao, where the stone lay, he declared:

Naha Stone art thou:

And by Naha Prince only may thy, sacredness be broken.

Now behold, I am Kamehameha, a Niu-pio

A spreading mist of the forest.

So fierce was his struggle with the stone that ‘blood burst from his eyes and from the tips of his fingers and the Earth trembled with the might of his struggling,’ according to the Legend of the Naha Stone, translated by Rev Stephen Desha. Some thought he was aided by an earthquake, a clear sign of divine intervention. Even so, the stone was overturned ‘so that all who stood by were amazed and dumb with awe’. The feat was taken as a portent of his greatness to come.

But his triumph was not guaranteed. Succession could be bloodthirsty affairs, and like his uncle Kalaniopu’u, who had come to power by right of conquest, Kamehameha had to fight for his throne. Long before he became The Conqueror, he had won a reputation as a fighter, helping to put down rebellions against his uncle. When Kalaniopu’u died, Kamehameha was still only second in line, after his cousin Kiwala’o. But he held an important religious position, and challenged the new King by stealing the mana of a sacrificed ali’i. A brief war erupted that led to the battlefield death of Kiwala’o. The Big Island descended into civil war, though at least Kamehameha started with the largest part of the island.

Defeat of the Fair American

He married Kaahumanu eight years after Cook’s flesh was stripped from his bones, and three years after his cousin’s death at the battle of Moku’ohai. The daughter of an allied chieftain on Maui, the second largest island, she was at his side three years later when he captured a US merchantman, the Fair American, with its cannons and metal weapons, and two British sailors.

Captain Simon Metcalf of The Eleanora, and his son Thomas, who commanded the Fair American, had arranged to meet at Hawaii should they become separated. This happened after they were observed smuggling furs from Spanish colonies. The father arrived at Hawaii first in Eleanora and incurred the enmity of the islanders by flogging a chief and firing a broadside that killed a hundred or so people.

The Hawaiians were understandably in an undiplomatic mood when Thomas, turned up later in the Fair American. After giving the captain a feathered helmet, the local chief, Kame’eiamoku, threw the unsuspecting American overboard. His men did the same with the crew, and the canoeists below beat those who could swim to death with their paddles. Only one was allowed to survive – Welshman Isaac Davis, who had acquitted himself as a noble warrior.

When Simon Metcalfe, unaware of his son’s fate, returned to a nearby bay, he sent his boatswain, John Young, ashore to seek trade. But Kamehameha, wary of retribution for the attack on the Fair American, captured Young and refused to let anyone make contact with the ship. Captain Metcalfe gave up after a few days and abandoned his boatswain to his fate.

Originally from Liverpool, Young would become a powerful figure in Hawaiian society and a key ally of Kaahumanu. According to Emeritus Professor Barbara Bennett Peterson of the University of Hawaii, he was The Conqueror’s 'most trusted advisor', in part because of his quick grasp of Hawaiian society, culture and language. Along with Davis, he was granted ali’i status and numerous lands and titles. He served as governor of the Big Island (Davis got O’ahu) when The Conqueror was on one of the other islands, and was eventually appointed Prime Minister, guiding Kamehameha to adopt a pro-British foreign policy.

When he was later offered passage to England, Young politely declined, having made a good life for himself on Hawaii, with two wives and six children. He was at the King’s deathbed, and supported Kaahumanu’s bid for power.

Although not entirely in the service of The Conqueror out of their own free will (at least to begin with), Davis and Young had an immense effect on Kamehameha’s fortunes. Crucially, they trained his army and navy, their experience with British discipline giving his forces an edge. In one naval battle, Kamehameha destroyed the opposing fleet even though it too was armed with European weapons.

Kaahumanu was not a passive wife during her husband’s meteoric rise. Although she enjoyed pastimes such as surfing and making kites, the King’s favourite was a power behind the throne. She sat on his council and, says Hawaiian historian Samuel Kamakau, was the 'pillar and cornerstone of his government', squarely behind the wars of unification.

But she was not above helping her relatives. Her influence at court led the king to appoint her first cousin, Kalanimoku, (known as ‘Billy Pitt’), as his second in command. ‘Billy Pitt’ earned his nickname because of his regard for Britain’s William Pitt the Younger, and because they both served as prime minister to their respective monarchs. Like both Kaahumanu and his namesake, he possessed a first-rate mind and soon mastered western languages and manners, making him an invaluable link between the king and foreign visitors.

Kamehameha and Kaahumanu had one child, born in the twenty-second year of their marriage – the same year Liholiho was acknowledged as heir apparent. But their daughter was never destined to rule. Liholiho’s mother, Keopuolani, possessed the ‘purest’ bloodlines on the Islands, making her status almost godlike. Even Kamehameha had to strip to his waist just to enter her presence. But while her son would succeed his father, Keopuolani was never a serious political threat. As a sign of his continued respect, the king named Kaahumanu Liholiho’s guardian.</span>

Unification of the Hawaiian state was completed in 1810, a year after the birth of Kaahumanu's daughter. The Conqueror’s final victory was over Kauai, which he forced into vassalage. His last few years were devoted to consolidating his power and preparing for the continuation of his dynasty.

The king adopted the trappings of a modern state, including a flag with nine horizontal stripes and a Union Jack in the canton (the current version has eight stripes, one for each island). The inclusion of the British flag highlights the influence London had. Kamehameha had ‘ceded’ Hawaii to Britain 16 years before unification, turning his kingdom into a protectorate. The British reciprocated by helping him to modernised his army. He gave his soldiers uniforms and firearms, and built forts and batteries for the country’s defence.

International trade was also high on his agenda. Sandalwood was the kingdom’s cash crop, and he kept it as a royal monopoly. As well as this lucrative export, the King made money from port and harbour fees.

Kamehameha established his seat of government on the west coast of the Big Island, with a residential complex at Kamakahonu. It had a place of worship, huts for chiefs, and the Hale Nana Mahina’ai, his residence and the only place he would sleep. All the buildings were in the traditional thatched style. It was here that he spent the last years of his life.

Thus his son Liholiho inherited a prosperous and independent realm. But the new king was no conqueror. Kamehameha II was known to have dissolute tendencies, and was more likely to be found drinking rum than ruling. Diplomats could hardly remember an audience when he was sober.

Possibly, the dying Kamehameha asked his favourite wife to share power with his son for this very reason. Female chieftains were not unheard of, so the law did not prohibit the move. But her claim, at his installation ceremony, to know the will of the late sovereign is unsubstantiated. Some historians think she just made it up.

Whether or not it was an audacious coup d’état, it paid off and Kaahumanu was named kuhina-nui. Though translated as regent, co-ruler, or prime minister, in truth this title gave Kaahumanu more authority than any premier. She controlled virtually all day-to day affairs and the ‘special interests’ of the Kingdom. In effect, she was the Queen Regent.

The fall of kapu

Despite the formalisation of her power, she was by no means secure. An iconoclast, she had long been at odds with Hawaiian customs and religion, and those who enforced it. The system of kapu was a complex list of foods and behaviours that were forbidden to certain classes and groups of people. Some kapus were permanent, while others could be imposed temporarily, sometimes over an entire island. The word is a cousin of ‘taboo’, which English adopted from the Tongan language. The Hawaiian word was first recorded by Cook on his ill-fated visit.

Kapu protected the monarchy and the ali’i. It prevented commoners, for instance, from crossing the king’s shadow, or that of the house where he lived. It also restricted women; one of the most rigidly enforced kapus was a prohibition against men and women eating together. Hawaiians were disgusted when they first saw this while travelling in Europe or the Americas.

Kaahumanu had already violated kapus such as the bizarre prohibition against eating bananas. The proscriptive list was so long that it would be impossible not to have transgressed in some way. She was also perceptive enough to notice that foreigners broke these sacred rules repeatedly without divine punishment; indeed, they seemed happier and healthier for it. Kaahumanu realised that to enjoy her rule unconstrained, she would have to destroy the system, starting with the rule against separate eating.

"Preferred methods

of human sacrifice

included strangulation,

bone breaking, and

disembowelment"

She made her move at the feast celebrating her stepson’s accession. Standing, she addressed the new King, saying that she and her followers 'resolved to be free' to be able to eat food cooked in the same oven and food that was prohibited. If this was not enough, she ended with 'let us henceforth disregard kapu'.

It was a gamble, and the stakes could not have been higher. If she won, Kaahumanu would overthrow a centuries-old culture, if she lost, her life could be forfeit, since the breaking of any kapu was punishable by human sacrifice. Preferred methods included strangulation, bone breaking, and disembowelment. But Kaahumanu was lucky in her allies. She had enlisted the King’s mother in her revolution. Keopuolani’s near-divine lineage placed her at the pinnacle of the kapu system. So when she brought her youngest son, Kauikeaouli, six, to eat among the women at the feast, no one dared stop her.

The Queen Mother also had a lot to lose. But in Captive Paradise, A History of Hawaii, author James Haley argues that ‘she was never awed by the sanctity of the forbidden’. She refused to give her daughter to a nanny, despite the kapu ’uha, which decreed death to any child she personally reared.

In the end, rather than endorsing or condemning these actions, the new King absented himself. When he later dedicated a new temple, the Queen Regent sent him a note denouncing the god. Realising the position he was in and unable or unwilling to act against both the Queen Mother and the Queen Regent, Kamehameha did what he did best; he went on a two-day drunken binge.

While the King was in a stupor, Kaahumanu lobbied the most powerful chiefs and the high priest to agree an end to kapu. Only then did she send messengers to fetch her stepson. Facing the inevitable and swallowing his pride, Kamehameha II agreed to share a meal with the women. And with that, the islands’ entire way of life was abolished.

The enormity of this religious revolution cannot be over stated. In the words of one eye witness, it presented 'a singular spectacle of a nation without a religion'. Soon the priesthood was abolished, temples were desecrated and up to 40,000 idols were destroyed or sold to European collectors.

It was not, however, a bloodless revolution. Resistance formed around the priesthood, who launched an abortive rebellion. But the old order was no match for the well trained and equipped royal forces which the King had inherited from The Conqueror. The military crushed the rebels and nipped any remaining dissent in the bud.

"As many as two-thirds

of infants were

murdered before their

second birthdays"

Kaahumanu’s rule was now fairly secure. She had won the chiefs around by ending the royal monopoly on sandalwood, creating a middle-class who were invested in the new regime. Abolishing kapu also had the happy consequence of ending human sacrifice.

Her next step was almost as drastic. Missionaries had been shocked to learn that unwanted children were buried alive by their parents. As many as two-thirds of infants were murdered before their second birthdays. The reason given was often simply the ‘trouble of bringing them up’, said Congregationalist missionary William Ellis. Kaahumanu banned the practice, though it was a decade before it entered the statute books.

Tragedy of a jester in London

Kamehameha II, meanwhile, was at best a figurehead and at worst the court jester. He led a non-stop, drunken, costumed carnival around the kingdom. The main royal duty he had performed was incestuously marrying his half-sister, Kamamalu (a niece of Kaahumanu) thereby keeping the royal bloodline ‘pure’.

Ever whimsical, the King conceived the idea of visiting his fellow monarch, George IV, in London. He chartered the 475-ton British whaler L’Aigle and set sail with his new bride and an entourage of eight other dignitaries, including Kama’ule’ule, better known as Boki. As the governor of O’ahu, Boki had been a loud opponent of European influence, except when it came to alcohol. He was one of the King’s favourite drinking companions.

After many stormy weeks at sea they reached the British capital. Britain was then at the height of its power, having beaten Napoleon at the battle of Waterloo only nine years previously. The streets of London were lined with carriages and shops filled with products from Britain’s growing empire. Gaslights were still a relatively new addition to the urban landscape, but the sewage system was rudimentary, and it would be 13 years before the first railway would reach the city at Euston.

The royal couple and their entourage took up residence at Osborn’s Hotel, near the Thames. They indulged their spare time by playing cards, smoking cigars and watching a Punch and Judy puppet show. The press and the public were fascinated, partly due to the visitors’ size and dress. The women wore feathered turbans and loose robes while the men sported stockings and black coats in keeping with the fashions of the ali’i. The men were tall and “exceedingly stout” while the women were even taller than the men and “equally fat and course made”. The couple enjoyed showing themselves at their window so much that the manager of the hotel had to apply to the magistrates for protection from the crowds they drew.

Frederick Byng, an eccentric member of the foreign office, was assigned to escort them around London. Byng was a curious choice as he was known for his gaffes, often insulting a host’s food, house or, servants. He had married his mother’s maid and was nicknamed “poodle” on account of his curly hair. The foreign secretary, George Canning, also threw a lavish party for the King and Queen of Hawaii, whose guests included the Duke of Wellington, hero of Waterloo.

George IV deliberately delayed his meeting with the “damn’d cannibals”. In the end, Kamehameha and his Queen caught measles, a disease unknown on the islands, and died within a week of each other at their hotel. George IV met the remaining delegation, including Boki, whom he treated with courtesy, before they departed to Hawaii on HMS Blonde.

Although there was an outpouring of grief in Hawaii when the news became known, it made little difference politically. Kaahumanu was used to exercising power as Queen Regent and the new situation only enhanced her power. The late king’s brother, Kauikeaouli, by then twelve, became the new monarch as Kamehameha III; he too would need the guiding hand of his stepmother.

In order to retain the loyalty of the old vassal king of Kaua’i, the widowed Kaahumanu had married him before Kamehameha II departed for England. Although she was apparently charmed by the handsome old gentleman; the privilege of being kuhina-nui meant that she was also able to take his son as a second husband. He was six foot and athletic, one of the handsomest men on the islands. This is something she had not been able to get away with before. Once, when The Conqueror was distracted by his other wives, she had taken a nineteen-year-old lover. But Kamehameha was a jealous husband, and killed the youth.

Zeal of a convert

Having destroyed one religion, Kaahumanu spent her later years embracing another – Christianity. Protestant missionaries had been arriving on the islands since the 1820s in growing numbers. Kaahumanu had held an interest in Christianity for many years and, like the Roman Emperor Constantine, was baptised the year after Kamehameha II died in London. She took Elizabeth for her Christian name, possibly in reference to the famed and feared Queen of England.

Though a zealous convert, the Queen Regent did not adopt humility; she arrived at church services in a carriage pulled by exhausted lackeys. As a sign of her baptismal commitment, she divorced her handsome young husband (Her older husband, the chieftain of Kaua’i, had died the year before.) and lived the rest of her life as a pious widow.

Kaahumanu had moved the seat of power permanently from the Big Island of Hawaii to Lahaina on Maui, the island of her birth. There she resided in a traditional, thatched hale pili, refusing to live in the two-storey brick palace built a few feet away by The Conqueror.

Conversion to Congregationalism had made the de-facto ruler of Hawaii implacably hostile to Catholicism. Under the influence of her protestant mentors, Catholic missionaries were deported and converts were jailed. Adultery was prohibited with a law against ‘mischievous sleeping’, although it grandfathered existing polygamous, and polyandrous, relationships. And her opposition to the native religion continued with the prohibition of hula dancing, which was dedicated to the goddess Laka. In the long run, the rain goddess won that one.

She instituted a new system of law, including acts against theft and murder, reflecting key tenets of the Ten Commandments, and personally sat as judge over the islands’ first jury trial.

Kaahumanu died in 1832, just two years after this act was passed. Her legacy was tremendous. Ralph Kuykendall, in his seminal work on The Hawaiian Kingdom, described her as 'the most imposing figure amongst the native rulers of Hawaii' possessing an 'autocratic temper' which had allowed her to govern her people with 'a rod of iron'.

Her presence can still be seen today with churches, a highway, and even a shopping centre bearing her name, the last boasting an eight foot statue. Her more immediate legacy was the preference for a female kuhina-nui, her successor in that office being her niece Kinau. The office was officially incorporated into the Hawaiian constitution in 1840.

Kaahumanu had gone from one of 30 wives of a local chief to the ruler of all Hawaii, her influence spanning three monarchs, forging the early destiny of the island kingdom. Though things would arguably start to go downhill after her death, with the eventual incorporation of Hawaii into the United States, she will always be remembered as a staunch defender of her country, if not of Kapu.